1DONE: Spatial and temporal discretisation¶

The real-world space and time continua are discretized in the ORCHIDEE model. Discretisation serves one or several of the following purposes: it allows for a rational use of the computational resources, it helps to better account for heterogeneity, and it enhances the simulation of highly non-linear processes. The spatial and temporal discretisation of the model has far-reaching consequences for its scope, its numerical approaches, and its computational costs.

Typical resolutions for global scale simulations range between 0.1 ° x 0.1 ° and 2.0 ° x 2.0 ° which is a trade-off between data availability of the boundary conditions (section 1) and the exponential increase in computation cost for higher resolution grids. At such resolutions each individual grid cell contains in reality different: (1) vegetation types, (2) soil types, (3) hydrological catchments, (4) elevations, (5) hillslope aspects, and (6) groundwater depths. This heterogeneity is addressed through the discretisation of the model. When an increase in model resolution is supported by high resolution boundary conditions (section 1), it is likely to better account for spatial and temporal heterogeneity. However, at higher resolution the validity of several of the structural model assumptions (section 1) is at risk.

1.1DONE: Land surface¶

The domain of an ORCHIDEE simulation is represented by an equidistant or unequal grid of cells where the number of cells will depend on the resolution of the grid. The domain of an ORCHIDEE simulation can range from a single grid cell representing a few 100 m2 of vegetation to thousands of grid cells describing a specific region or the global landmass. The grid and its resolution are implicitly set through the choice of the climatic forcing. If ORCHIDEE is coupled to an atmospheric model, it uses the same grid as the atmospheric model. If ORCHIDEE is run as a land-only model, its grid is identical to the grid of the meteorological forcing. A land-sea mask is applied to extract all terrestrial grid cells within the domain. The land-sea mask gives the continental fraction (; unitless) of each grid cell and only grid cells with > 0 will be considered by ORCHIDEE.

1.2DONE: Vegetation classes¶

ORCHIDEE accounts for the heterogeneity of the vegetation in each grid cell by combining fractions of plant functional types (PFTs) as proposed by Prentice et al. (1992). Land cover products that are prepared to be used in ORCHIDEE prescribe the fraction of each PFT within that grid cell (; unitless). The distribution of PFTs comes from historical land cover reconstructions, contemporary remote sensing products, future land cover maps, or a combination of these sources (see 1.2). The product used to prescribe the PFT distribution should have the same number of PFTs as the model configuration, unless age classes are used (section 1.3).

At the highest hierarchical level, vegetation is classified in 13 meta-classes (MTCs). Each MTC can be split in a user-defined number of PFTs. Different PFTs that offspring from the same MTC will differ by at least one parameter value. For all other parameters, the PFT inherits the values of the MTC it originates from. This hierarchical approach has been exploited to introduce new PFTs in several applications, including regional ones Naudts et al., 2016Luyssaert et al., 2018, to account for age classes in forest MTCs Naudts et al., 2016Luyssaert et al., 2018 or to assess gross land cover changes Yue et al., 2018. ORCHIDEE currently uses its 13 MTCs to create 15 PFTs (including one PFT for bare soil, eight PFTs for various combinations of leaf-type and climate zones of forests, four PFTs for various climate zones and photosynthetic pathways for grasslands, and two PFTs for different photosynthetic pathways for croplands). Although PFTs differ in their parameter values, they mostly share the same equations with exceptions for the calculation of photosynthesis for C3 and C4 plants, leaf phenology, and leaf senescence.

The sum of all PFT fractions where individual fractions could be zero, should be less or equal to one:

If the sum of fraction is less than 1, the remaining fraction of the grid cell is considered as a non-biological fraction () and is treated as glacier.

Following finalisation of the integration of lakes, future version of ORCHIDEE, will read a surface functional type map (SFT) instead of the current PFT map. One of the SFTs will then be lakes. For the time being, the lake fraction in each gridcell is read through a separate map (See 1.5). When ORCHIDEE pre-processes its PFT maps, lakes are placed on bare soil. If the the bare soil fraction cannot satisfy the areal demand of lakes in that grid cell, lakes are placed on grassland PFTs. The addition of lakes thus reduces the share of bare soil and grasslands in the grid cells where lakes are present.

1.3DONE: Age classes¶

At the beginning of a simulation, the number of age classes, the number of circumference classes, and the MTCs for which more than one age class will be used have to be set by the user. Although not all MTCs need to be run with several age classes, all MTCs that are run with age classes have the same number of age classes. The number of circumference classes is the same for all forest PFTs and is fixed to one for grassland and cropland PFTs.

If age classes are used in the simulation, all PFTs representing different age classes of the same vegetation should be matched by a single PFT on the land cover map (See 1.2). This implies that the age class distribution is an emerging property of the simulation.

For each forest MTC, several age class can be defined. Within an MTC, each age class is simulated as a separate PFT. Contrary to what its name suggests, the age class boundaries are determined by the tree diameter rather than the age of the trees. Different age classes are distinguished to better account for forest succession and its effects on the carbon, nitrogen, energy and water fluxes. For example, when several age classes are used, forest regrowth following land-cover change, forest management, or a natural disturbance will end up in a separate age class. However, when a single class is used, the regrowth is mixed with the mature vegetation typically diluting the effect of regrowth on forest structure and thus albedo, roughness length, and evapotranspiration to mention a few.

1.4DONE: Diameter classes¶

Each forest PFT in ORCHIDEE contains a mono-specific forest stand that is structured by a user-defined but fixed number of circumference classes (, three by default). Throughout the simulation, the boundaries of the circumference classes are adjusted to accommodate changes in the stand structure, while the number of classes remains constant. Flexible class boundaries provide a computationally efficient approach to simulate different forest structures. For instance, an even-aged forest is simulated by using a small diameter range between the smallest and largest trees, resulting in all trees belonging to the same stratum. In contrast, an uneven-aged forest is simulated by applying a wide range between diameter classes such that different classes represent different canopy strata. Circumference classes are taken into account in ORCHIDEE v4.2 to better simulate canopy structure. Since the canopy acts as the interface between the land and the atmosphere, this feature has implications that extend beyond forest management. The structure of the stand has been shown to influence albedo, transpiration, photosynthesis, soil temperature, roughness length, and recruitment Amiro et al., 2006Amiro et al., 2006Otto et al., 2014Luyssaert et al., 2014Ahlström et al., 2020Toda et al., 2023.

PFTs are simulated independently from each other with the sole exception that all forest PFTs share the same water column. Consequently, the water consumption of one forest PFT affects the water availability of all other forest PFTs. Because age classes are simulated as PFTs in ORCHIDEE v4.2, this implies that also the age classes of the same MTC are competing for soil water (See 1.6).

1.5DONE: Vertical canopy layers¶

The canopy space of each PFT is discretised in a user-defined number (, ten by default) of equidistant vertical canopy layers that start at the top of the crown of the tallest individual in the PFT and extend to the bottom of the crown of the smallest individual in the PFT or 0.001 m in case of grassland and cropland PFTs. The calculation of the crown and canopy dimensions as well as the leaf area contained in each vertical canopy layer is detailed in section 1.5.7.

1.6DONE: Soil water columns¶

Each grid cell distinguishes three independent soil water columns also referred to as soil tiles. A soil water column is linked to the vegetation discretization such that each of the 13 vegetation meta-classes (MTC) is associated to a single soil water column, and each of the three columns gather distinct types of vegetation; one soil water column is reserved for the bare soil MTC, one for tree-based MTCs, and one for grass and crop MTCs. The soil water content and all processes controlling its dynamics (i.e., infiltration, root uptake, diffusion, etc.) are calculated independently for each soil water columns, which do not communicate horizontally with each other. This enables limiting competition between bare soils, tree-based MTCs and graas and crop based MTCs for water resources in the soil Boucher et al., 2020, as well as allowing for differences in root profiles between these soil water colums Rosnay, 2002d'Orgeval et al., 2008. Note that the different MTCs within a single soil water column, compete for water among each other.

1.7DONE: Soil texture classes¶

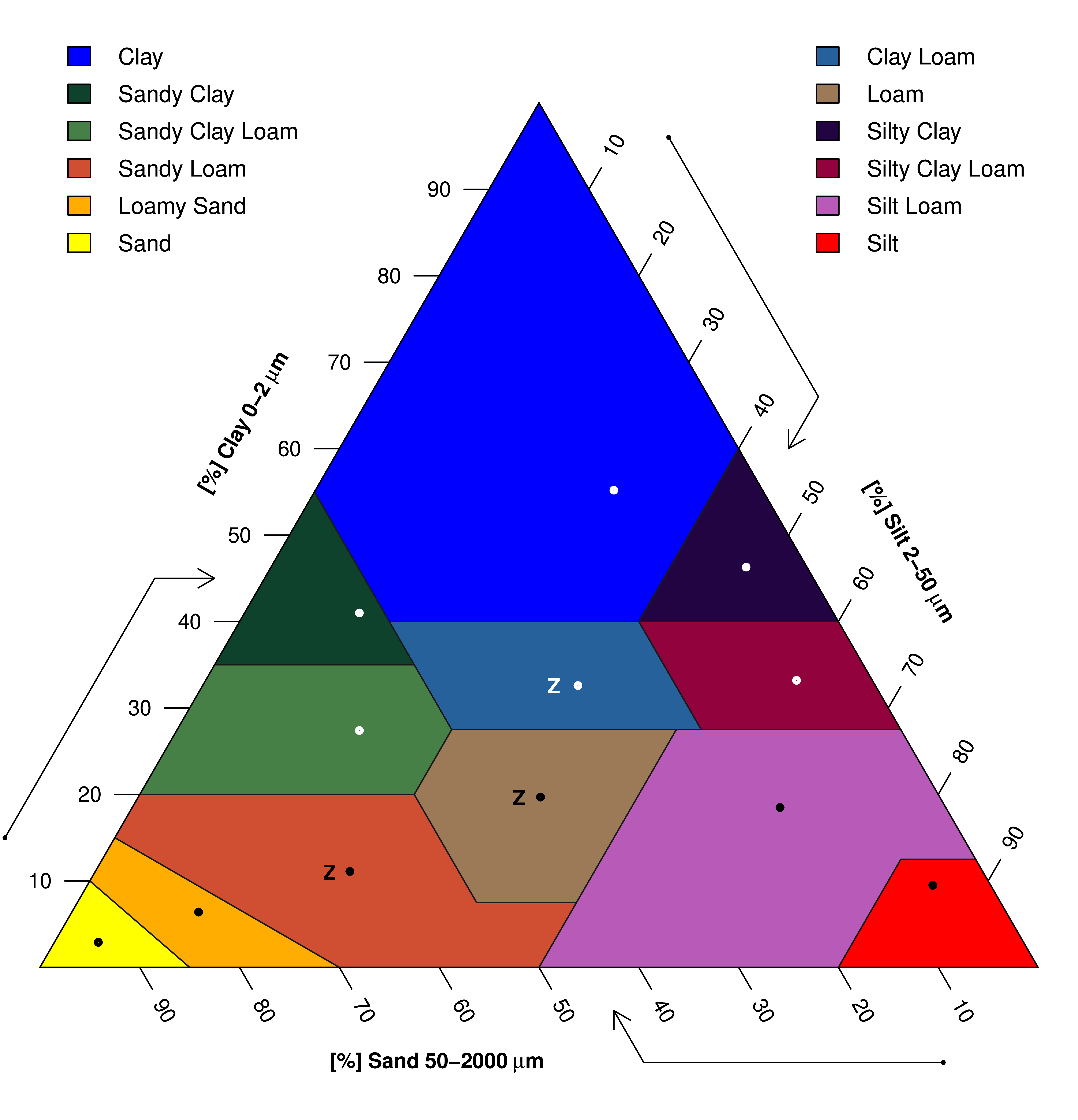

Figure 1:Correspondence between the soil granulometric composition and the USDA textural classes. "Z" denotes the three classes of the simplified classification (coarse, medium, and fine, corresponding to sandy loam, loam, and clay loam, respectively).

Two soil texture classifications are available in ORCHIDEE: (1) the default scheme consisting of US Department of Agriculture (USDA) textural classes. For this, the map of Reynolds et al. (2000) is adapted for use in ORCHIDEE by splitting the clay texture class into regular (swelling) clay and clay oxisols according to the FAO Soil Order Map Tafasca, 2021. After this split the map distinguishes 12 textural classes plus oxisols: sand, silt, clay loam, loamy sand, loam, sandy clay, sandy loam, sandy clay loam, silty clay, silt loam, silty clay loam, clay, and oxisols. (2) A simplified scheme based on Zobler (1986) consists of only three textural classes, i.e., coarse, medium, and fine, corresponding to USDA sandy loam, loam, and clay loam, respectively. In both cases, the textural class is determined by the relative proportions of three granulometric fractions: sand (particle diameter between 0.05 mm and 2 mm), silt (diameter between 0.002 mm and 0.05 mm), and clay (diameter below 0.002 mm). The correspondence between the granulometric composition and the USDA textural classes is shown in Fig. 1.

1.8DONE: Vertical soil layers¶

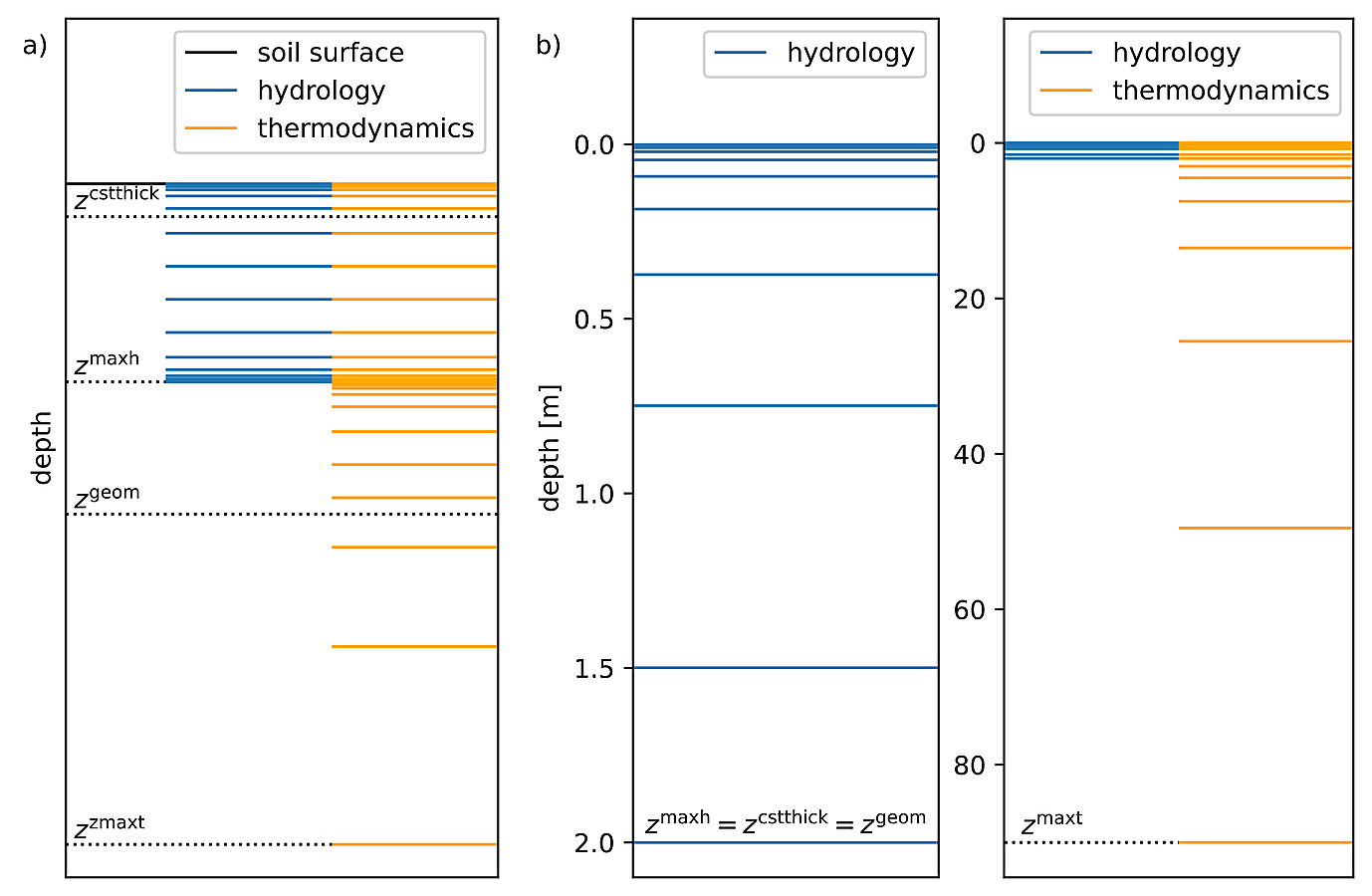

Figure 2:a) General and b) default vertical discretisation for soil hydrology and soil thermodynamics.

ORCHIDEE solves the equations of heat and water transport in the soil in one dimension using a finite difference method. For this, it uses a staggered grid consisting of nodes — at which water content and temperature are calculated — and of layer boundaries — at which heat and water fluxes are calculated.

The general layering scheme for hydrology is shown in Fig. 2a. It extends down to and consists of layers whose thickness increases geometrically with a ratio of 2, starting from a prescribed thickness of the first layer. Optionally, the geometric increase in thickness can be stopped below a depth of , producing layers with constant thickness. These can optionally be followed by layers with decreasing thickness (the decrease is geometric with a ratio of 1/2). The optional layers with constant thickness and the refinement at the bottom are intended for configurations with an impermeable bottom, in which a water table and thus a strong moisture gradient can form anywhere in the soil column. The hydrological layers of the default ORCHIDEE configuration are shown in Fig. 2b. The default configuration uses a free-drainage boundary condition and thus only layers with a geometrically increasing thickness. The thickness of the first layer , and , resulting in 11 layers.

Since ORCHIDEE v2.0, the thermodynamic soil layering is identical to the hydrological one in the region where the two overlap, but extends further to a depth of Wang et al., 2016. As shown in Fig. 2a, this extension consists of layers that increase in thickness mirroring the refinement at the bottom of the hydrological soil column (if the refinement is used), followed optionally by layers with constant depth down to , below which the geometric increase in layer thickness resumes. In the default configuration, shown in Fig. 2b, and the thermodynamic layers continue the geometric progression of the thickness of hydrological layers, reaching a depth of with a total of 18 layers. ES: should a sentence here be added to explain the soil C and N discretization or bucket? or it has been decided that it should be explained elsewhere?

1.9DONE: River basins¶

For the lateral transport of water over the continents and down to the oceans, the resolution of the climatic forcing is typically too coarse to allow a good representation of the topography, which is the main driving factor for the water surface flows. ORCHIDEE features two different approaches for the spatial discretisation of the river basins.

The first approach, which is often used when ORCHIDEE is used in an ESM-configuration, is to disentangle the grid of the climate forcing or climate simulations, on which the one-dimensional vertical water fluxes are computed, and the grid on which the lateral river routing is done. In the latter grid, the river basin discretisation follows the cells of the input hydrological digital elevation model (HDEM; See 1.6) or an aggregation of these cells. The water fluxes and pools are exchanged between the two grids through interpolations, ensuring mass conservation as proposed by Kritsikis et al. (2017). This approach is referred to as the "interpolated" routing method in ORCHIDEE. Not clear how many river basins we have, which is the actual discretisation. "In a typical global configuration this approach distinguishes XX rivers."

The second approach is a hybrid approach that uses a sub-grid tiling of the climatic forcing or the climate simulations to reach the resolution required for the hydrological lateral transfers Ngo-Duc et al., 2007Polcher et al., 2023. Within the supermesh of the HDEM grid cells overlapping with the coarser ORCHIDEE grid, a multistep algorithm is used to build, sub-divide, and merge elements that eventually constitute a sub-basin dimension Polcher et al., 2023.

In fact, each ORCHIDEE grid cell is thus discretised into at most hydrologically consistent and connected tiles, yielding graphs of hydrological transfer units (HTUs) along which the water flows within and from grid cell to grid cell. This is referred to as the "subgrid" routing methods in ORCHIDEE. Not clear how many river basins we have, which is the actual discretisation. "In a typical global configuration this approach distinguishes XX rivers."

describe here or in the spatial discretisation that there is a slow flow from the groundwater and a fast flow from the runoff that all enters the rivers.

1.10DONE: Lakes¶

Given the standard spatial resolution of several tens of kilometres in ORCHIDEE, the model distinguishes different lakes classes. The number of lake classes us a user-defined setting but by default ORCHIDEE distinguishes three classes according to the depth if the lakes. This choice was driven by the results of a prior sensitivity analysis with the FLake model REF showing that lake depth was the main parameter that affected the surface energy budget and fluxes, followed by some radiative properties such as the surface albedo or the extinction coefficient Bernus et al., 2021. The three classes are representative of shallow (< 5 m), medium, and deep lakes (> 25 m).

1.11DONE: Elevation, aspect and groundwater depth¶

Although ORCHIDEE reads a digital elevation model, elevation differences within a grid cell are not taken into account except for the pre-calculation of the river basins (See 1.9). When using a stand-alone configuration, the differences in elevation between grid cells are implicitly accounted for through the climate reconstructions and explicitly through the topography index for the river routing calculations. The coupled land-atmosphere configuration considers differences in elevation between grid cells in its climate calculations and river routing.

The aspect of hill slope and groundwater depth are not taken into account in ORCHIDEE, neither the heterogeneity between grid cells nor the heterogeneity within a grid cell.

1.12DONE: time steps¶

ORCHIDEE combines three different time steps (Table 7): (1) few minutes (30 minutes for stand-alone simulations and less than 20 minutes when coupled to a GCM), (2) daily, and (3) annual. The minutes-scale processes include the soil water budget (for each soil column) and the exchanges of energy (for each grid cell), H2O and CO2 through photosynthesis (for each PFT in each grid cell) between the atmosphere and the biosphere. They also account for litter decomposition and soil carbon dynamics. The daily processes include river routing for each watershed but mostly calculate the carbon dynamics of the terrestrial biosphere and essentially represent processes such as growth respiration, carbon allocation and phenology (all calculated for each PFT in each grid cell). The annual processes simulate changes in the land cover, wood harvest, mortality of PFTs and establishment of new PFTs as part of global vegetation dynamics.

SL: table needs to be updated to contain all (sub)titles from the model description

PP: thinks that there is maybe some sub-stepping for the hydrology. Can someone confirm?

- Prentice, I. C., Cramer, W., Harrison, S. P., Leemans, R., Monserud, R. A., & Solomon, A. M. (1992). Special paper: a global biome model based on plant physiology and dominance, soil properties and climate. Journal of Biogeography, 117–134.

- Naudts, K., Chen, Y., McGrath, M. J., Ryder, J., Valade, A., Otto, J., & Luyssaert, S. (2016). Europe’s forest management did not mitigate climate warming. Science, 351(6273), 597–600.

- Luyssaert, S., Marie, G., Valade, A., Chen, Y.-Y., Njakou Djomo, S., Ryder, J., Otto, J., Naudts, K., Lansø, A. S., Ghattas, J., & others. (2018). Trade-offs in using European forests to meet climate objectives. Nature, 562(7726), 259–262.

- Yue, C., Ciais, P., Luyssaert, S., Li, W., McGrath, M. J., Chang, J., & Peng, S. (2018). Representing anthropogenic gross land use change, wood harvest, and forest age dynamics in a global vegetation model ORCHIDEE-MICT v8. 4.2. Geoscientific Model Development, 11(1), 409–428.

- Amiro, B., Barr, A., Black, T., Iwashita, H., Kljun, N., Mccaughey, J., Mogenstern, K., Murayama, S., Nesic, Z., & Orchansky, A. (2006). Carbon, energy and water fluxes at mature and disturbed forest sites, Saskatchewan, Canada. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 136(3–4), 237–251. 10.1016/j.agrformet.2004.11.012

- Amiro, B. D., Orchansky, A. L., Barr, A. G., Black, T. A., Chambers, S. D., Chapin III, F. S., Goulden, M. L., Litvak, M., Liu, H. P., McCaughey, J. H., McMillan, A., & Randerson, J. T. (2006). The effect of post-fire stand age on the boreal forest energy balance. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 140(1–4), 41–50. 10.1016/j.agrformet.2006.02.014

- Otto, J., Berveiller, D., Bréon, F.-M., Delpierre, N., Geppert, G., Granier, A., Jans, W., Knohl, A., Kuusk, A., Longdoz, B., Moors, E., Mund, M., Pinty, B., Schelhaas, M.-J., & Luyssaert, S. (2014). Forest summer albedo is sensitive to species and thinning: how should we account for this in Earth system models? Biogeosciences, 11(8), 2411–2427. 10.5194/bg-11-2411-2014

- Luyssaert, S., Jammet, M., Stoy, P. C., Estel, S., Pongratz, J., Ceschia, E., Churkina, G., Don, A., Erb, K., Ferlicoq, M., Gielen, B., Grünwald, T., Houghton, R. A., Klumpp, K., Knohl, A., Kolb, T., Kuemmerle, T., Laurila, T., Lohila, A., … Dolman, A. J. (2014). Land management and land-cover change have impacts of similar magnitude on surface temperature. Nature Climate Change, 4(5), 389–393. 10.1038/nclimate2196

- Ahlström, A., Fälthammar-de Jong, G., Nijland, W., & Tagesson, T. (2020). Primary productivity of managed and pristine forests in Sweden. Environmental Research Letters, 15(9), 094067.

- Toda, M., Knohl, A., Luyssaert, S., & Hara, T. (2023). Simulated effects of canopy structural complexity on forest productivity. Forest Ecology and Management, 538, 120978.

- Boucher, O., Servonnat, J., Albright, A. L., Aumont, O., Balkanski, Y., Bastrikov, V., Bekki, S., Bonnet, R., Bony, S., Bopp, L., & others. (2020). Presentation and evaluation of the \uppercaseIPSL-CM6A-LR climate model. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems, 12(7), e2019MS002010.

- de Rosnay, P. (2002). Impact of a physically based soil water flow and soil-plant interaction representation for modeling large-scale land surface processes. Journal of Geophysical Research, 107(D11), 4118. 10.1029/2001JD000634

- d’Orgeval, T., Polcher, J., & De Rosnay, P. (2008). Sensitivity of the West African hydrological cycle in ORCHIDEE to infiltration processes. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 12(6), 1387–1401.

- Reynolds, C., Jackson, T., & Rawls, W. (2000). Estimating soil water-holding capacities by linking the Food and Agriculture Organization soil map of the world with global pedon databases and continuous pedotransfer functions. Water Resour. Res., 36, 3653–3662.

- Tafasca, S. (2021). Evaluation de l’impact des propriétés du sol sur l’hydrologie simulée dans le modèle ORCHIDEE [Phdthesis]. Sorbonne Université.