1OK: Disturbances¶

1.1DONE: Drought¶

In ORCHIDEE v4.2 one out of two approaches to calculate plant water stress needs to be chosen by the user: a soil-atmosphere or a soil-plant-atmosphere approach. If the soil-atmosphere approach (section 1.3.1) is selected, a soil water stress logistic function, using a soil water potential at wilting point , is used as a proxy for plant water stress. The direct impact of soil water stress on the photosynthesis is accounted for by reducing the maximum carboxylation rate. A relationship between soil water and maximum carboxylation rate is not supported by observational evidence. If the soil-plant-atmosphere approach (section 1.3.3) is selected, the plant water stress is calculated, by explicitly calculating the potentials and resistances of the plant organs, and controls jointly photosynthesis and transpiration through its control on stomatal conductance, which is function of the leaf water potential. The relationship between soil water and stomatal conductance is supported by observational evidence Rodriguez-Dominguez et al., 2016. Irrespective of the approach, ORCHIDEE v4.2 only accounts for the direct effects of soil water stress on photosynthesis. Plant strategies and their associated carbon and nitrogen costs to avoid plant water stress, e.g., leaf shedding, or to cope with the impacts of plant water stress, e.g., cavitation, or legacy effects of droughts have not yet been implemented. At present only long sustained droughts result in vegetation mortality in ORCHIDEE through carbon starvation.

1.2OK: Wind throw¶

In ORCHIDEE v4.2 the calculation of wind throw and subsequent tree mortality is optional. If wind throw is simulated, the model calculates the critical wind speed based on the principles applied in ForestGALES Gardiner et al., 2000, and storm damage based on the approach developed and tested by Anyomi2017. The wind throw module is composed of several components. The first step is the detection of a storm (section 1.2.1). Once a storm is detected, the calculation of wind speed and gustiness provide proxies for potential damage (sections 1.2.2 and 1.2.3). Next, the susceptibility of the grid cell to wind damage is assessed by considering the soil and root characteristics, forest gaps, and forest edges (section 1.2.4 and 1.2.5). Finally, storm damage is calculated and the damaged biomass is move to either the litter or harvest pools depending on the forest management (sections 1.2.6 and 1.2.7).

1.2.1OK: Storm detection¶

The storm detection algorithm performs three tasks: (1) mimicking vegetation adaptation in areas frequently exposed to strong winds, (2) distinguishing between long-lasting storms and shorter gusts, and (3) linking events occurring at consecutive time steps of different days.

Particularly in coastal areas, high wind speeds persist. In response to frequent wind exposure, vegetation growing in these areas tend to grow adaptive capacities by adjusting the height and shape, reducing their vulnerable to strong wind conditions Bonnesoeur et al., 2016Gardiner et al., 2016. However, ORCHIDEE v4.2 does not yet account for such adaptations (section 1 "Evolutionary assumption"). To address this issue, the ratio of the actual wind speed to the mean wind speed at each location is used instead of the actual wind speeds. By calculating the relative wind speed, generally high wind-speed grid cells require a much higher wind speed to experience damage compared to grid cells in areas with lower mean wind speeds, thus implicitly mimicking the effect of vegetation adaptation.

The duration of high relative wind speed is a defining characteristic of storminess. It is assumed that trees exposed to strong winds for extended periods are more likely to be uprooted or broken. To account for this effect, the relative half-hourly wind speed is summed over the course of the day (ORCHIDEE v4.2 is driven by half-hourly wind fields) for every time step it exceeds its threshold. This approach yields a daily count between zero and 48 half hours exceeding the threshold wind speed ratio. This count is used to classify the daily wind conditions as a storm or not.

The model calculates wind damage at the last time step of the day, with the original module using the daily maximum wind speed to compute the damage Chen et al., 2018. However, if a storm event spans multiple days in the forcing, the model would repeatedly calculate wind damage, leading to an overestimation of the damage. This issue required a more dynamic approach to detecting the start and end of a storm event. ORCHIDEE v4.2 now calculates the daily sum of the relative wind speed over three days. If the 3-day sum exceeds the threshold, and the daily maximum wind speed surpasses the threshold, the module recognizes the beginning of the storm.

Once the module detects the start of a storm, it waits for the daily maximum wind speed to drop below the threshold. Once the wind speed decreases, the module waits until it remains below the threshold for 5 days. If the wind speed exceeds the threshold within 5 days, the process of detecting the end of the storm restarts. If the wind speed does not exceed the storm threshold for 5 days after a storm is detected, the storm is considered over, and the damage caused by the storm is calculated. This approach results in a 5 day delay between the end of the storm and the moment the damage is accounted for.

1.2.2OK: Critical wind speeds¶

The presence or absence of storm damage in a forest stand is modeled using the concept of critical wind speed Gardiner et al., 2010. If the wind speed exceeds the critical wind speed of a forest, the forces applied may be sufficient to overturn the whole tree or break its stem. The exact value of the critical wind speed depends on the canopy structure Vollsinger et al., 2005Hale et al., 2012, the tree species, the soil properties and the root profiles Nicoll et al., 2006. The physics formalized in ForestGALES Gardiner et al., 2010Hale et al., 2015, a hybrid mechanistic forest wind damage risk model, is included in ORCHIDEE v4.2. This approach simulates the critical wind speeds of all forest stands for two types of damage: tree uprooting and stem breakage. The critical wind speed for uprooting is calculated as:

Where (m s) is the critical wind speed for uprooting. (unitless) is the von Karman constant Foken, 2006 and (m) is the inter-tree spacing. (N m kg) is a regression coefficient that was derived from tree pulling experiments Nicoll et al., 2006, where N stands for Newton. (kg) is the green mass of the bole of the tree. is calculated by multiplying the simulated above-ground biomass with green density for different tree species Chen et al., 2018. is air density (kg m) and is a unitless gust factor described in section 1.2.3. (unitless) is the enhanced momentum caused by the overhanging displaced mass of the canopy. In ORCHIDEE v4.2, is set to 1.136, taken from the results of extensive tree-pulling data Nicoll et al., 2006. is a unitless factor to account for the edge effect on gustiness (section 1.2.3). (m) is the tree height, (m) is the the displacement height, (m) is the roughness length (section 1.4.2). The critical wind speed for stem breakage is calculated as:

Where (m s) is the critical wind speed for stem breakage, (Pa) is the PFT-specific modulus of rupture of green wood Chen et al., 2018. (m) is the tree diameter at breast height as simulated by ORCHIDEE v4.2 and is a unitless factor to reduce wood strength due to the presence of knots.

The roughness of the canopy for momentum and displacement height is calculated follow the analytical relationships proposed by Raupach, 1994:

where, (unitless) is dependent on canopy characteristics (equation %s) and (unitless) is the atmospheric stability correction function Raupach, 1994 and is calculated as:

Where (m s) represents wind speed at the top of the canopy, (-) is a constant, (m) is crown width and (m) is crown depth. Tree crowns, branches and stems are considered as porous and flexible materials that will streamline and change their shape with changing wind speeds (). Streamlining was parameterised through the parameters and (-), which are reported for wind tunnel experiments with different tree species Rudnicki et al., 2004Vollsinger et al., 2005. represents a reduction in the drag coefficient from a reduction in canopy area due to streamlining its minimum values is set at 10 and the maximum at 25 where these limits are based on the wind speed range reported in Mayhead1973. The species specific streamlining effect for a wind speed outside this range was calculated by holding constant, using the lower or upper threshold. and depend on the wind speed at canopy height hence iterations are required to solve equation 428 and 429.

Critical wind speeds are calculated as the solutions of a non-linear set of equations for uprooting, i.e., equations 428, 431 and 430, and another set of equations for stem breakage, i.e., equations 429, 431 and 430. An initial wind speed () of 25 , is applied to equation 431 and equation 430 to obtain an approximation for by applying equation 428. Similarly, an initial wind speed () of 25 , is applied to equation 431 and equation 430 to obtain an approximation for by equation 429. Subsequently, is set to the value of (or ) to estimate the aerodynamic parameters ( and ) for the next iteration. The iteration process is stopped if the difference in between two iteration falls below 0.01 or the number of iterations exceeds 20.

Whereas ORCHIDEE v4.2 is designed to simulate both even-aged and uneven-aged stands (see section 1.10.1), the original model Gardiner et al., 2010 is limited to simulating the critical wind speeds for even-aged forests. Although this design difference is expected to have minimal impact, it becomes important in the calculation of the ratio between tree height and tree spacing (known as inter-tree spacing, ). In even-aged stands, both tree height and tree spacing are uniform and well-defined at the stand level, whereas in uneven-aged stands, tree height is no longer uniform. In ORCHIDEE v4.2, the largest diameter class represents the dominant trees that form the canopy and hold the majority of the stand’s biomass. Therefore, the critical wind speed is calculated only for this dominant diameter class. To calculate the inter-tree spacing for this class, the total woody biomass at the stand level is calculated. This total biomass is then divided by the biomass of the modeled trees in the largest diameter class. The resulting value is used as the virtual inter-tree spacing, , in equation(428) and equation(429) to calculate the critical wind speeds.

ORCHIDEE v4.2 calculates the critical wind speed for both breakage and uprooting, based on the vegetation structure parameters. Two critical wind speeds are computed for each forest in each grid cell, and the lower of the two is used to determine the type of damage to the PFTs. Biomass loss is then calculated by multiplying the damage rate (; see section 1.2.6) by the total biomass of the PFTs, with the biomass loss accounted for from the largest to the smallest diameter class. The number of damaged trees is calculated based on the biomass loss rate.

1.2.3DONE:Gustiness and edge effect¶

ORCHIDEE v4.2 is driven by half-hourly wind fields. Such a time step averages out the extreme wind gusts that occur within a half-hour. Because storm damage is primarily influenced by extreme wind gusts rather than the average wind speed, this scaling issue is addressed by considering gustiness. Unlike the original module from Chen et al. (2018), ORCHIDEE v4.2 uses a simple modifier to account for gustiness ():

(m s) represents the maximum wind speed over the last three days (see section 1.2.1), and (m s is the extreme wind gust that is compared with the critical wind speed to calculate damage.

The edge effect is considered at the landscape level. Within each grid cell, forests are separated into two regions, i.e., the inner area and the outer area. For the area bordering the gap (see section 1.2.5), the effect of vegetation structure on wind speed is accounted for using the edge factor in equation428 and equation429. The calculation of follows the approach proposed by Gardiner et al. (2000):

where represents the distance of the forest to the nearest forest edge. For the forest area away from the gap, the edge effect is negligible such that is set to 1.0.

1.2.4DONE: Soil characteristics¶

Although ORCHIDEE v4.2 distinguishes 13 soil classes (see section 1.7), the current approach to simulating soil water hydrology, De Rosnay et al. (2003) assumes all soils are free-draining at the bottom of the soil layers. This differs from the original model Gardiner et al., 2010, which distinguishes four soil classes with varying drainage properties: freely draining mineral soil, gleyed waterlogged and oxygen-deficient mineral soil, peaty mineral soil, and deep peat Hale et al., 2015. Currently, ORCHIDEE only uses parameters for freely draining mineral soils. As a result, ORCHIDEE is expected to overestimate the critical wind speed and thus underestimate damage in areas with shallow or wet soils.

Additionally, the original model formulation in ForestGALES Gardiner et al., 2010Hale et al., 2015 differentiates between shallow, medium, and deep rooting species. This classification is applied in ORCHIDEE v4.2 via the parameter that describes the vertical root profile. The storm damage calculation make use of the structural root profile (see section 1.5.10) that follows a truncated exponential decay from the top to the bottom of the soil layers, independent of site conditions or stand age. PFTs are considered shallow-rooted if 90 % of their total root mass is above a depth of 2 m. Under the current settings, the wind throw module assumes that all PFTs are shallow-rooted. The effect of rooting depth on critical wind speeds is accounted for by using different regression coefficients, , for shallow and deep-rooting species. When the soil is frozen, the model only simulates windstorm damage from stem breakage, meaning no tree uprooting is possible. The soil is deemed frozen based on the temperature at 0.8 m below the surface, which serves as the threshold.

1.2.5DONE: Forest gaps¶

Vegetation structure is simulated at both the landscape level and the stand level. At the landscape level the simulations distinguish between forests with a newly formed forest edge and forest with established edges. Edges result from natural or anthropogenic stand replacing disturbances. First, the surface area of stand replacing disturbances is accumulated over the last 5 years ( ()), a time horizon corresponding to the time required for forests nearby newly formed edge to adapt to the increased gustiness Gardiner & Stacey, 1996. By prescribing the average gap size (; ) to 2 ha (20000 m), and assuming gaps are square shaped and the gustiness is affected over a distance of 9 times the canopy height () Gardiner & Stacey, 1996, the forest area that experiences an increased gustiness due to proximity of recent gaps ( ()) is calculated as:

Where the factor of accounts for the fact that only the downwind edge perpendicular to the wind will experience an increased gustiness. The second term is the area bordering a single gap and the third term is the total number of gaps in the grid cell. The forest area that has no edges in its proximity (; ) is calculated as the residual:

Where (m) is the area of the simulated grid cell.

1.2.6DONE: Storm damage ¶

When wind speeds approach the critical wind speed, damage such as defoliation and branch damage become more likely. Once the wind speed exceeds the critical wind speed, uprooting and stem breakage are possible but their likelihood increases with further increasing wind speeds. A sigmoid damage function is applied to simulate the rate of storm damage to a forest, which was proposed and tested by Anyomi2017 for estimating storm damage as a function of the daily maximum wind speed. This relationship is formalized as:

Where (unitless) is the damage rate and thus the share of trees that will be killed, (unitless) is an observed maximum damage rate which was set to 0.8 but scales to the size of an individual grid cell in ORCHIDEE. Where a damage rate of 0.8 is likely at the hectare scale, it is unlikely for a 2 ° pixel. is a relaxation parameter to adjust the damage rate given by a certain wind speed below the model calculated critical wind speed, and a value 6.0 was applied for all PFTs. is the maximum daily wind speed from the forcing or the atmospheric model. Subsequently, the lowest out of the six calculated critical wind speeds (see section 1.2.2), is used to determine the damage type for each diameter class. The number of damaged trees in each diameter class () is then calculated by multiplying the damage rate () with the tree numbers within each diameter class. The total stand density damaged by a storm is, therefore, the number of damaged trees per unit of ground area summed across each diameter class.

1.2.7DONE: Moving biomass to litter and harvest pools¶

Damaged trees due to storms are left on site in unmanaged forests, however, salvage logging is often carried out for a managed forest in order to recover some of the economic losses and avoid large scale insects outbreaks triggered by wind disturbance Lindenmayer et al., 2012. When dealing with the effects of wind damage on the biomass pools of forests, the subsequent anthropogenic response is accounted for. ORCHIDEE v4.2 distinguishes managed and unmanaged forest (see section 1.4). In unmanaged forests all carbon contained in trees killed by wind storms end up in the litter pools following equations 376 and %s.

For managed forests, salvage logging is implemented according to equations 419 to %s where , i.e., the branch ratio is replaced by which prescribes the ratio of the stem that is salvaged logged. During salvage logging not only the branches are left on site but also part of the stems is left because they no longer have an economic value due to stem breakage Nieuwenhuis & Fitzpatrick, 2002Dubrovskis et al., 2018, hence is lower than .

In species that are prone to bark beetle attacks following wind throw (see section 1.3), the volume left on site is very small. In Sweden, a maximum volume of 5 newly damaged logs is allowed Fridh, 2006. However, following large-scale storm damage this threshold has been temporarily lowered to 3 in order to reduce the risk of spruce bark beetle outbreaks Fridh, 2006. Given that the current implementation of storm damage was designed to deal with large wind storms, with a fair risk for subsequent bark beetle outbreaks Kärvemo, 2015, applying a very high efficiency for salvage logging, i.e., 99 %, appears justified Schroeder et al. (2006).

1.3DONE: Bark beetles¶

1.3.1DONE: Life cycle of a bark beetle outbreak¶

In ORCHIDEE v4.2 the calculation of bark beetle outbreaks and subsequent tree mortality is optional. If bark beetle disturbances are calculated, the life cycle of an outbreak includes the following stages (Fig. 15):

a) the endemic stage at which the forest stand experiences low bark beetle pressure enabling the forest to maintain a pseudo-climax or climax depending on whether the stand is managed or not (shown as stage 1).

b) The build-up stage is characterised by a rapid increase in the bark beetle population due to an event that weakened part of the trees but without visible impact on healthy trees (stage 1 & 2). Although in reality wind storms and drought are typical events to initiate the start of the build-up stage, ORCHIDEE v4.2 only considers wind storms as a possible trigger for an increase in the beetle population.

c) During the epidemic stage bark beetles are so numerous that they can successfully attack healthy trees causing a change in leaf colour (stage 2 & 3).

d) In the post-epidemic stage a significant reduction in the bark beetle population occurs due to a lack of substrate for feeding and breeding (stage 3 & 4). Stage 4: In the gray stage infected trees that retain their leaves and remain standing, gradually die turning into so-called snags. Stage 5: in the ecological transition stage degradation from wind throws and bark beetles result in openings in the canopy reducing-between tree competitions. In Stage 6 bark beetles return to their initial population level resulting in a new endemic stage during which recruitment may help the forest to reach a (pseudo-)climax stage.

Figure 15:Life cycle of a bark beetle outbreak and subsequent dynamics of a forest stand

1.3.2DONE: Implicit representation of bark beetle populations¶

The bark beetle breeding indicator of the current year (; unitless) is calculated from a logistic function, which depends on the number of generations a bark beetle population can sustain within a single year:

Where () and () are tuning parameters for the logistic function, represents the sum of effective temperature for bark beetle reproduction in ° C day, while denotes the thermal sum of degree days for one bark beetle generation in ° C day. Saturation of represents the lack of available breeding substrate when many generations develop over a short period.

Bark beetles, which tend to breed earlier when winter and spring were warmer, can produce multiple generations in the same calendar year Hlásny et al., 2021. This pattern is accounted for in the calculation of , which is calculated from January 1 until the first generation’s diapause, triggered when day length exceeds 14.5 h (e.g., April 27th for France). Each day prior to this diapause with a daily average temperature around the bark above 8.3 degree C () and below 38.4°C () is accounted for in the summation of :

Where is the day, is the number of days between January 1st and the day of the diapause. The optimal bark temperature for beetle development is set at 30.3° C and is the bark temperature below which beetle development stops. is the average daily bark temperature, calculated as the daily average air temperature minus 2° C. All parameter values are taken from Temperli et al., 2013.

The bark beetle pressure indicator (unitless) is formulated based on two components: (1) the and (2) an indicator of the loss of tree biomass in the previous year due to bark beetle infestation (; unitless) which is thus a proxy of the previous year’s bark beetle activity. The expression accounts for the legacy effect of bark beetle activities by averaging activities over the current and previous years. In this approach, the susceptibility indicator (; unitless) serves as an indicator for increased bark beetle survival which could result from favorable conditions for beetle demography (see next section).

The bark beetle activity of the previous year (; unitless) is calculated as:

Where (g m) is the biomass killed by bark beetles during previous year, (g m) is the total biomass of the stand, and and are parameters that drive the intensity of this negative feedback.

During the build-up of the epidemic i.e stage in which bark beetles population is high enough to mass attack healthy tree, the population of bark beetles can either return to its endemic i.e. stage in which beetles population is at the lowest, if tree defense mechanisms are preventing bark beetles from successfully attacking healthy trees, or evolve into an epidemic stage, if the tree defense mechanisms fail. During the post-epidemic stage, the forest is still subject to higher mortality than usual, but signs of recovery appear Hlásny et al., 2021. Recovery may help the forest ecosystem to return to its original state or switch to a new state with different species or a change in forest structure depending on the intensity and frequency of the disturbance Van Meerbeek et al., 2021. ORCHIDEE v4.2 was shown of being capable of simulating a change in forest structure Marie et al., 2023 but cannot simulate a species change.

1.3.3DONE: Bark beetle survival¶

The capability of bark beetles to survive the winter in between two breeding seasons is critical in simulating epidemic outbreaks. During regular winters, winter mortality for bark beetles is around 40 % for the adults and 100 % for the juveniles Jönsson et al., 2012. In our representation, this mortality rate is implicitly accounted for in the calculation of the bark beetle survival indicator (; unitless). A lack of data linking bark beetle survival to anomalous winter temperatures justifies an implicit approach and prevented including this information as a modulator of . The latter explains why winter temperatures do not appear in equation 438. Instead, the model simulates the survival as a function of the abundance of suitable tree hosts, which decreases the competition for shelter and food:

The availability of woody necromass from trees that died recently, particularly following windstorms, plays a critical role in bark beetle survival and proliferationBouget & Duelli (2004). In the year following a windstorm, uprooted and broken trees may offer an ideal breeding substrate for bark beetles, facilitating their population growthReid & Robb (1999). In Temperli et al. (2013), an empirical correlation between windthrow events and bark beetle susceptibility was used. ORCHIDEE enhances realism by considering the actual suitable hosts, i.e., living or recently died trees, as the primary driver of bark beetle survival. To avoid overestimating bark beetle population growth, the parameter (unitless) which corresponds to the maximum fraction of the living biomass that could be killed by bark beetles, is introduced. Any addition of dead trees beyond is considered ineffective in affecting the bark beetle population. This ensures that an excess of breeding substrate does not artificially inflate beetle numbers. This relationship is quantitatively represented in ORCHIDEE through the dead host indicator, , which is driven by the availability of recent dead trees. The formulation of is as follows:

where, (g m) represents the quantity of woody necromass from the current year, (g m) is the total living woody biomass in the stand, and is the threshold at which the ratio is at the maximum level.

This indicator captures the immediate increase in dead trees suitable for bark beetle breeding following a windthrow event. However, Dead wood is most suitable for bark beetle breeding within the first year after tree death. During this periodReid & Robb (1999), the wood retains higher moisture content and nutritional quality, which are critical for beetle reproductionSiegert et al. (2018). This is accounted for by excluding woody necromass that is older than 1 year from the calculation of .

The parameter is a scale dependent parameter. The mortality rate of trees that will trigger an outbreak is very different across spatial scales. Where a relatively high share of dead wood is needed to trigger an outbreak at the patch-scale, a much lower share of dead wood suffices at the landscape-scale to trigger a widespread bark beetle outbreak. So these parameters must be set according to the spatial resolution of the simulation experiment. Currently, the parameter is fixed to 0.2 based on the evaluation of large European simulation scale.

The alive host indicator is driven by two factors: (1) the abundance of weak trees, which can be more easily infected by bark beetles, and (2) the ability of bark beetles to attack healthy trees. denotes the survival of bark beetles, which is facilitated by the abundance of suitable trees, reducing the competition among bark beetles for breeding substrates and therefore increasing their survival.

The indicator represents the ability of bark beetles to attack healthy trees when the number of bark beetles is large enough. This indicator only depends on the size of the bark beetle population (equation 439):

controls the steepness of the relationship, while is the bark beetle pressure indicator at which the population is moving from endemic to epidemic stage where mass attacks are possible. The epidemic stage corresponds to the capability of bark beetles to mass attack healthy trees and overrule tree defenses Biedermann et al., 2019. At this point in the outbreak, all trees are potential targets irrespective of their health. Three causes have been suggested to explain the end of the epidemic phase: (1) the most likely cause is high interspecific competition among beetles for tree hosts when the density is decreasing komonen2011, resulting in a decreasing in ORCHIDEE; (2) a series of (very) cold years will decrease the ability of the beetles to reproduceŠtefková et al. (2017) which is simulated in ORCHIDEE through a decreasing ; and (3) a rarely demonstrated increasing population of beetle predators Berryman, 2002. In ORCHIDEE v4.2, the first two causes are represented but the last, i.e., the predators, is not.

ORCHIDEE does not explicitly represent weak trees, but tree health is thought to decrease with increasing stand density given the stand diameter. The indicator for host suitability is thus calculated by making use of the relative density index :

represents the steepness of the relationship, and is a parameter for the relationship between stand rdi and beetle susceptibility. is used to estimate the average competition between trees at the stand level. At an (unitless) of 1, the forest is expected to be at its maximum density given the carrying capacity of the site, implying the highest level of competition between trees. The calculation of follows equation 342 but is limited to the spruce PFTs:

Where (unitless) is the current tree density of an age class , (unitless) represents the maximum stand density of a stand given its diameter (see equations 339 and %s), (unitless) is the fraction of spruce in the grid cell that resides in this age class and is the fraction of spruce within a grid cell. The number of age classes () within a vegetation meta class (MTC) is four when demographic succesion is activated (section 1.10.1).

1.3.4DONE: Host attractivity¶

The stand attractivity indicator () represents how interesting a stand is for a new bark beetle colony and is calculated as follow:. When tends to 0, the stand is constituted mainly by healthy trees which are less attractive for beetles, whereas an approaching 1 represents a highly stressed spruce stand suitable for colonization by bark beetles.

Where (unitless) indicates the stress the trees experience due to within-stand resource competition and (unitless) represents the ability of the host to set up a defense against a bark beetle attack. Factors that contribute to the stress of a forest and its ability to guard off beetle attacks include nitrogen availabilityMason et al. (2019), limited carbohydrate reservesErbilgin et al. (2021), age structureNetherer et al. (2019), and tree species diversityJaime et al. (2022). Trees experiencing extended periods of environmental stress are expected to have fewer carbon and nitrogen reserves available for defense compounds, making them vulnerable to bark beetle attacks even at relatively low beetle population densities Raffa et al., 2008. Nonetheless, the reserve pools in ORCHIDEE v4.2 have not yet been evaluated, so the and is calculated by using proxies such as 1-year drought modulator (; unitless) and a relative density index ():

Where is the average daily plant water stress indicator over the growing season for the spruce stand. When is equal to 0 or 1, plants are highly stressed or not stressed, respectively. represents the steepness of the relationship, and is the plant water stress below which the health of the stand will be affected.

In addition to drought, overstocking may also decrease the overall healthiness of a spruce stand ().

Where represents the steepness of the relationship, and represents the limit at which the bark beetle outbreak starts to decline because of a lack of suitable host trees. The severity of bark beetle-caused tree mortality decreases when going from the stand to the landscape scale. At the landscape scale, covering areas of 10 to 10 km, the duration of mortality may be longer and the severity lower because beetles disperse across the landscape and cause mortality at different times. This distinction is important for interpreting model results, particularly when considering parameters like in the ORCHIDEE model. describes the proportion of trees surviving after an outbreak and should therefore be adjusted for the spatial scale of a grid cell in ORCHIDEE. In a model set-up where a grid cell represents a single stand ( 1 ha), should be close to 0, indicating that nearly all trees may be killed. However, in a simulation with grid cells representing 2500 km, not all trees will be killed, which is reflected in setting , in this example, to 0.4. Equation 449 is close to %s, but the parameter is reduced by a factor of two in order to reflect that is more sensitive to than .

The indicator (used in equation 447) takes into account that in a mixed tree species landscape, even a few non-host trees may chemically hinder bark beetles in finding their host trees Zhang & Schlyter, 2004, explaining why insect pests, including Ips typographus outbreaks, often cause more damage in pure compared to mixed stands Nardi et al., 2023. ORCHIDEE v4.2 does not simulate multi-species stands but does account for landscape-level heterogeneity of forests with different PFTs. The bark beetle model in ORCHIDEE assumes that within a grid cell, the fraction of spruce over other tree species is a proxy for the degree of mixture:

where represents the steepness of the relationship, and are prescribed parameters TO EXPLAIN

1.3.5DONE: Bark beetle damage¶

The biomass of trees killed by bark beetles in one year and one grid cell (; g m) is calculated as the product of the probability of a successful attack (; see next section) averaged over the number of spruce age classes , the biomass of trees attacked by bark beetles (; g m) and weighted by their fraction . The approach assumes that a successful beetle colonization results in the death of the attacked trees, which is a simplification from reality Leufvén & Nehls (1986).

During the endemic stage, the biomass of attacked trees () and killed trees () are at their lowest level and the damage from bark beetles has little impact on the structure and functioning of the forest. Biomass losses from bark beetles can be considered to contribute to the background mortality.

is the outcome of bark beetles that successfully overcame the tree defenses and succeeded in boring holes in the bark in order to reach the sapwood. is calculated at the grid cell by multiplying the actual stand biomass of spruce () and the probability that bark beetles attack spruce trees in the grid cell (; unitless).

represents the ability of the bark beetles to spread and locate new suitable spruce trees as hosts for breeding. is calculated by the product of two indicators: (1) the stand attractivity indicator (; see equation 447) which reflects the ability of the forest to resist an external stressor such as bark beetle attacks and (2) the beetle pressure indicator (; see equation 439) which is a proxy for the bark beetle population.

1.3.6DONE: Tree mortality from bark beetle infestation¶

When bark beetles attack a tree, the success of their attack will depend on the capability of the tree to defend itself from the attack. Trees defend themselves against beetle attacks by producing secondary metabolites Huang et al., 2020. The high carbon and nitrogen costs of these compounds limit their production to periods with environmental conditions favorable for growth Lieutier et al., 2002. The probability of a successful bark beetle attack is driven by the size of the bark beetle population () and the health of each tree. ORCHIDEE, however, is not simulating individual trees but rather circumference classes within an age class. An indicator of tree health for each age class (; unitless) was calculated as:

Except during mass attacks, trees rarely die solely from bark beetle damage as female beetles often carry blue-stain fungi, which colonize the phloem and sapwood, blocking the water-conducting vessels of the tree Ballard et al., 1982. This results in tree death from carbon starvation or desiccation. As ORCHIDEE v4.2 does not simulate the effects of changes in sapwood conductivity on photosynthesis and the resultant probability of tree mortality, the indicator of weakened trees () makes use of two proxies adjusted to be calculated only for one age class at a time:

To assess the bark beetle damage rate (; unitless), is divided by . The number of dead trees from bark beetles attack is updated from where only trees with a diameter above 0.07 m can be kill.

1.3.7DONE: Moving biomass to litter and harvest pools¶

Trees attacked by bark beetles are left on site in unmanaged forests, however, salvage logging is common in managed forest in order to recover some of the economic losses REF. When dealing with the effects of bark beetle outbreaks on the forest biomass, the anthropogenic response to is accounted for. ORCHIDEE v4.2 distinguishes managed (section 1.4) and unmanaged forest (section 1.6). In unmanaged forests all carbon contained in trees killed by bark beetles ends up in the litter pools following equations 376 and %s. For managed forests, salvage logging is implemented according to equations 419 to %s.

Figure 16:Is this useful? It is already outdated and it will be a pain to keep this up-to-date? A reference to Marie et al might be enough? If useful, this figure needs to be cited in the text Order of the calculations. The dotted line boxes represent the five main processes of the outbreak model as described in sections 1.3.2 to 1.3.6. The numbers correspond to the equation numbers in Marie et al., 2023. The variable names are listed in Marie et al. (2023) Table 1.

1.4DONE Fire¶

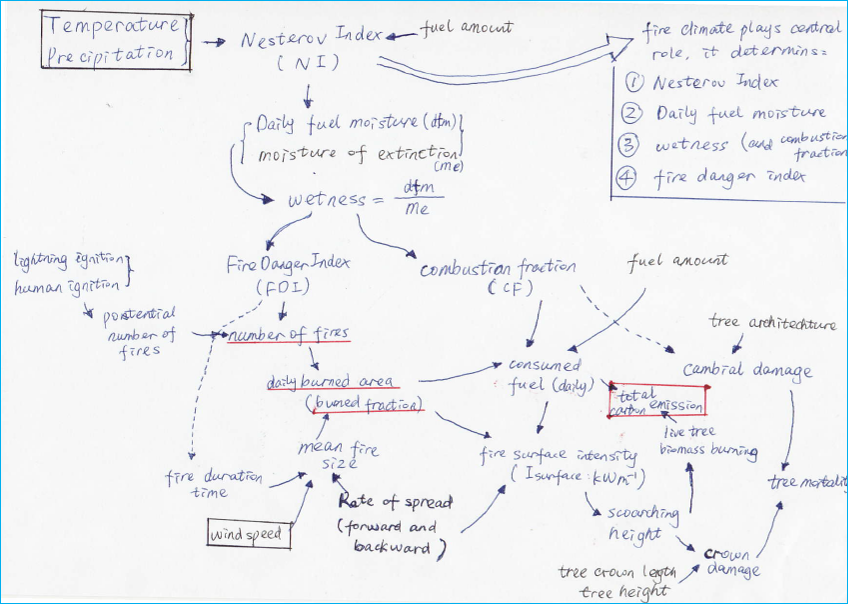

In ORCHIDEE v4.2 the simulation of fires and subsequent tdiree and grass mortality is optional. If fires are simulated, the approach in ORCHIDEE v4.2 is based on the SPITFIRE (SPread and InTensity of FIRE) model, initially developed by Thonicke et al. (2010) and integrated into an earlier version of ORCHIDEE Yue et al., 2014. Only key simulation processes are described below. For detailed information, please refer to Thonicke et al. (2010) and Yue et al. (2014).

Unlike models that simulate the native physical and chemical processes of vegetation combustion, such as chemical reactions during the combustion process, the associated energy processes during combustion, including radiation, and conduction and convection heating of unburned fuel, the SPITFIRE simulates surface fires through an empirical prognostic approach: (1) the model assumes a uniformly mixed fuel bed by integrating fuel characteristics of forest and grassland, rather than simulating burning process for each PFT (or forest age class) individually. Hence, no change in fire behavior is accounted for when fire front passes the boarder of different vegetation types. (2) Multi-day burning events are not explicitly modeled. Instead, SPITFIRE operates on a daily time step, with fires being started and extinguished over the same day. Fire weather and fire behavior are mostly determined by daily mean values of meteorological variables including wind speed, and hence any diurnal dynamics in fire behavior are ignored. (3) The daily burned area within a model grid cell is calculated as the product of fire number and fire size, assuming that all fires are independent burning events sharing the same size as determined by the steps of (1) and (2). The fire size is determined by fire spread rate and fire duration, assuming that fires start and extinguish within the same day. (4) The simulation of fire spread is based on an empirical surface fire spread model. Crown fire spread processes are not considered. (5) The surface fire spread model primarily applies to natural burning processes. However, because it is often implemented on a coarse grid, the effects of fire barriers—such as firebreaks, rivers, or bare soil separating cropland—are largely neglected in the simulation of fire spread. (6) For this reason, cropland burning is currently not included. (7) As the simulation of fire spread and resulting fire size is based exclusively on active burning, the associated estimates of carbon and trace gas emissions account only for emissions from active combustion; smoldering-phase emissions are mostly ignored.

The biogeochemical and biogeophysical impacts of fires are accounted for by simulating fire-induced forest and grassland mortality as well as the resulting carbon emissions. Part of dead trees and grasslands, and surface litter, are combusted directly by fire causing carbon and trace gas emissions from land to the atmosphere. Un-combusted biomass is transferred to litter. Following fire-induced mortality, it is mostly assumed that the pre-fire PFT will establish as explained in the section 1.10.3

1.4.1DONE: Fire weather and surface fuel moisture¶

Surface fuel, namely above-ground litter, is categorized into different classes based on the scale of time needed to reach a moisture level in equilibrium with the ambient environment: 1-hour (1h), 10-hour (10h), 100-hour (100h), and 1000-hour (1000h). The first three classes are ‘surface fine fuel’ whose moisture status determines fire likelihood and the resulting fire behaviour. Surface fuel moisture is determined through a prognostic relationship using meteorological variables. The Nesterov Index (NI) (unit: ℃2) is a meteorological dryness indicator calculated as (Thonicke et al. 2010):

where is the dew point temperature, and is the daily maximum temperature. The summation is accumulated for the period when daily precipitation remains lower than 3mm. The moisture content of surface fine fuel (, unitless, value range: 0–1) then depends on fuel composition and meteorological dryness (Thonicke et al. 2010):

where (gC m-2) represents the fuel load of each fuel type i of the surface fine fuel, is the total fuel load of surface fine fuel, and (℃-2) is proportional to the surface-area-to-volume ratio of different fuel types. The surface fine fuel moisture is then compared with the fuel moisture of extinction (, unitless), parameterized for each PFT, above which the surface fuel is too wet to allow any fire burning, in order to derive the fire danger index (FDI):

Figure 17:Is this useful? If so, this figure needs to be cited in the text Flow and dependencies of the fire calculations.

1.4.2DONE: The number of fires¶

Potential fire ignitions include human-induced incidents and lightning-induced natural ignitions (Yue et al.2014). The total number of potential ignitions per km2 and per day () is calculated as:

where and represent potential ignitions caused by human activity and lightning strikes, respectively. The monthly climatology of total lightning strikes, including both cloud-to-cloud and cloud-to-ground lightnings, derived from the Lightning Imaging Sensor–Optical Transient Detector (LIS/OTD), was utilized as the lightning input data (Yue et al. 2014). The number of potential lightning ignitions () is calculated as:

where represents the fraction of cloud-to-ground lightnings, represents the fraction of lightnings with sufficient energy to ignite a fire, and represents the fraction of lightning-ignited fires that are suppressed by human.

The human suppression on lightning fires () is calculated as a function of population density () following Li et al. (2012):

Human-induced potential ignitions () is also approximated as a function of population density ():

where represents the population density (individuals km-2), and denotes the potential number of fire ignitions per person per day. The parameter has regional specific values as parameterized in Thonicke et al. (2010). The role of humans to suppress fire ignitions is implicitly accounted for in the equation above, which prescribes a maximum number of ignitions when population density reaches 16 individuals km-2.

Apart from human suppression, fuel availability is also assumed to limit the success chance of a potential ignition through the ignition efficiency ():

where represents fuel load, denotes the lower threshold of fuel load, below which fuel availability is too small to allow any burning, and denotes the upper threshold of fuel load, above which fuel availability no longer limits ignition success. Between these two thresholds, the ignition efficiency linearly increases with fuel availability.

The number of fires () within a model grid cell for a given day, including both lightning- and human-caused ignitions and accounting for the influence of fire weather and fuel availability, is then calculated as:

where represents the area covered by forests and grasslands within a grid cell because cropland fires are currently excluded.

1.4.3DONE: Fire size¶

The simulation of fire size assumes that, on a daily time step, the burned patch developed from a single ignition source can be approximated by an ellipse with one of its two focal points being the ignition source. The major axis length of the burned ellipse can be calculated as the product of the fire spread rate, which is the sum of both forward and backward spread rates, and fire duration time. The length-to-breadth ratio of the ellipse is a function of surface wind speed.

The simulation of the forward surface fire spread rate (, ) consistent with the prevailing daily wind direction is based on a quasi-empirical surface fire spread model (Rothermel 1972), which is based on the conservation of energy described by a heat source divided by a heat sink:

where represents the reaction intensity, namely, the rate of energy release per unit area of the fire front ; \xi \ represents the propagating flux ratio (unitless), which is the proportion of the reaction intensity that heats neighboring fuel particles to the point of ignition under no wind conditions; is a unitless multiplier that accounts for the effect of wind in increasing the propagating flux ratio; \rho^{\mathrm{b}} \ is the bulk density of surface fine fuel, (unitless) is the effective heating number indicating the proportion of a fuel particle that is heated to ignition temperature at the time flaming combustion starts; is the heat of pre-ignition , which is the quantity of heat necessary to ignite a specific fuel mass (Rothermel 1972, Thonicke et al., 2010). The calculation of each of these variables is further detailed in Thonicke et al. (2010).

The rate of backward surface fire spread (, ), in a contrary direction to the daily prevailing wind, is calculated as:

where () represents the daily wind speed.

Fire duration (, in ) is simulated to increase with FDI but with a maximum fire duration time (), currently set as 241 minutes which represents the time limit of active afternoon burning, which cannot exceed a single day given that fire is simulated on a daily time step:

The distances (in ) of forward () and backward () surface fire spread are calculated as:

The length of the major axis of the burned ellipse is given by the sum of and .

The length-to-breadth ratio () of the elliptical fire scar is calculated as:

where and represent the relative fractions of forests and grasslands, and and represent the values of forests and grasslands, respectively:

The size of the fire patch (in ) is then calculated as follows:

Thus, the daily burned area() (in ) within a model grid cell is the product of the fire number and the (average) fire size:

1.4.4DONE: Carbon and trace gas emissions ¶

During active burning, the combustion of biomass fuel results in carbon and other trace gas emissions. Emissions from smoldering are in principle excluded because this phase of burning is not explicitly simulated. The carbon emissions from surface dead fuel, on a per burned area basis, are calculated as:

where and represents fuel load (gC m-2) and fuel combustion fraction (unitless) for different fuel classes (1h, 10h, 100h, and 100h).

The for 1h surface dead fuel is given by:

where represents the fuel moisture content (unitless) by combining 1h dead fuel with live grass fuel.

The values for surface dead fuel of 10h, 100h and 1000h are calculated as:

Additionally, the combustion fraction for 100h and 1000h surface dead fuels are further limited to a maximum value of 0.9 following Yue et al. (2014).

The combusted surface fuel is removed from litter pool, with proportional losses in nitrogen according to the C:N ratio of surface litter. Nitrogen emissions of various species from active surface fire burning is thus not accounted for, except for that NOx emissions are provided as a diagnostic variable (see below).

Carbon emissions in SPITFIRE includes forest crown scorching that is accounted for using a diagnostic approach (1.4.5). Other trace gas emissions(), including CO, CH4, VOCs, total particular matter (TPM), and NOx, are diagnostic variables derived using emissions factors:

where is carbon emissions from fire including those from both surface fuel and crown scorching; is emission factor that quantifies the ratio between trace gas emissions and carbon emissions.

1.4.5DONE: Forest mortality¶

Fire-induced tree mortality includes two aspects: cambial damage, and crown damage caused by flame crown scorching. Although only surface fire spread is simulated, the surface fire flame can reach a height comparable to tree crown and cause crown damage. The flame scorching height (, in ) scales with surface fire intensity (, ):

where is a PFT-specific constant parameter. Surface frontline fire intensity measures energy release per length of fire front and is derived empirically as:

where represents the heat content () of surface fine fuel (1h, 10h and 100h), denotes the combusted surface fuel in terms of dry matter calculated using and , means the fraction of vegetation area that’s been burned, is forward surface fire spread rate () which is converted to by being divided by 60.

As ORCHIDEE v4.2 represents forest stand structure using tree density and circumference classes and as tree diameter (), height () and crown length (or crown vertical diameter ) differ among circumference classes (see 1.5.6 and 1.5.7), the derivation of fire-induced tree mortality is thus made for each circumference class. Within each circumference class, the number of individual dead trees is determined by multiplying the derived mortality rate with its individual density.

The fraction of flame crown scorching () for the circumference class is derived by comparing the flame scorching height with tree height and canopy base height ():

Post-fire mortality from crown scorching (, unitless) for a given circumference class is calculated as:

where and are PFT-specific parameters.

Post-fire mortality from cambial damage is derived by comparing fire flame residence time (, minute) with tree-dependent critical residence time (, minute). The fire flame residence time is computed as:

where represents the combustion fraction for surface fine litter fuel, including 1 h, 10 h and 100 h fuel classes, is the reaction velocity () derived in simulating fire spread rate.

The critical residence time for fire fame is derived as:

where is the thickness of bark for trees of a given circumference class , which is calculated using the diameter at breast height ():

where and are PFT-specific parameters.

Forest mortality due to cambial damage is then calculated as:

Finally, post-fire forest mortality for a given circumference class , combing from both crown scorching and cambial damage, is derived by assuming that the two mortality causes operate independently:

The stand density killed by fire () is derived as:

where represents the stand density (individual ) for a given circumference class .

Due to crown scorching, part of live biomass, in particular small branches and leaves, are considered as being combusted, leading to carbon emissions to the atmosphere. The fractions of different biomass components that are directly combusted are prescribed in the model. The uncombusted dead biomass are transferred to corresponding litter pool.

1.5DONE: Herbivory¶

In ORCHIDEE v4.2 herbivory is optional. If herbivory is simulated, herbivore activity reduces the biomass of leaves and fruits of forest PFTs and leaves, fruits, and stalks of grass PFTs. In ORCHIDEE, cropland PFTs are not affected by herbivores and herbivory does not modify leaf age structure. To estimate edible biomass and herbivore consumption, the mean long-term leaf production is used McNaughton et al. (1989):

where (g C m s) is the consumption of biomass by herbivores, (unitless) is a fixed fraction of the leaves that is available to the herbivores, (g C m s K) and (unitless) are PFT-specific constants to calculate the herbivore activity as a function of 3-year mean net primary production (; g C m s). Herbivory is calculated daily, so (s) is the number of seconds in a day and (-) is a constant that differs between deciduous and evergreen PFTs to account for the length of the growing season. (s) is the time constant of the probability of a leaf to be eaten by a herbivore.

The consumption of biomass by herbivores and the resultant herbivore activity are calculated following:

where are the plant organs affected by herbivory - the leaves and fruits of forest PFTs and the leaves, fruits and stalks of grassland PFTs. Finally, the consumed biomass () is removed from the plant biomass and added to the litter pool.

1.6DONE: Individual tree vs. stand replacing disturbances¶

Damages from different disturbances are implemented as continuous functions that range from zero to the entire stand. If few individuals are damaged, the stand density is reduced. If, on the other hand, the damage exceeds 30 % of the total biomass, a new cohort is established in the youngest age class of the plant functional type when multiple age classes are present. Over several decades, disturbances contributes to the coexistence of different age classes within the same plant functional type. The 30 % threshold is somewhat arbitrary but based on observations that forests recover quickly after thinning 30 % of the basal area Vesala et al., 2005. Currently, this scheme is applied only to abrupt disturbances, such as wind damage, but will be extended to more gradual disturbances, like drought stress and bark beetle damage, in future versions of the model.

- Rodriguez-Dominguez, C. M., Buckley, T. N., Egea, G., de Cires, A., Hernandez-Santana, V., Martorell, S., & Diaz-Espejo, A. (2016). Most stomatal closure in woody species under moderate drought can be explained by stomatal responses to leaf turgor. Plant, Cell & Environment, 39(9), 2014–2026.

- Gardiner, B., Peltola, H., & Kellomäki, S. (2000). Comparison of two models for predicting the critical wind speeds required to damage coniferous trees. Ecological Modelling, 129(1), 1–23. 10.1016/S0304-3800(00)00220-9

- Bonnesoeur, V., Constant, T., Moulia, B., & Fournier, M. (2016). Forest trees filter chronic wind-signals to acclimate to high winds. New Phytologist, 210(3), 850–860. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13836

- Gardiner, B., Berry, P., & Moulia, B. (2016). Review: Wind impacts on plant growth, mechanics and damage. Plant Science, 245, 94–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.01.006

- Chen, Y.-Y., Gardiner, B., Pasztor, F., Blennow, K., Ryder, J., Valade, A., Naudts, K., Otto, J., McGrath, M. J., Planque, C., & others. (2018). Simulating damage for wind storms in the land surface model ORCHIDEE-CAN (revision 4262). Geoscientific Model Development, 11(2), 771–791.

- Gardiner, B., Blennow, K., Carnus, J., Fleischer, P., Ingemarson, F., Landmann, G., Lindner, M., Marzano, M., Nicoll, B., Orazio, C., Peyron, J., Schelhaas, M., Schuck, A., & Usbeck, T. (2010). Destructive Storms in European Forests : Past and Forthcoming Impacts. Final Report to European Commission - DG Environment (07.0307/2009/SI2.540092/ETU/B.1), January, 138. 10.13140/RG.2.1.1420.4006

- Vollsinger, S., Mitchell, S. J., Byrne, K. E., Novak, M. D., & Rudnicki, M. (2005). Wind tunnel measurements of crown streamlining and drag relationships for several hardwood species. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 35(5), 1238–1249. 10.1139/x05-051

- Hale, S. E., Gardiner, B. A., Wellpott, A., Nicoll, B. C., & Achim, A. (2012). Wind loading of trees: Influence of tree size and competition. European Journal of Forest Research, 131(1), 203–217. 10.1007/s10342-010-0448-2

- Nicoll, B. C., Gardiner, B. A., Rayner, B., & Peace, A. J. (2006). Anchorage of coniferous trees in relation to species , soil type , and rooting depth. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 36, 1871–1883. 10.1139/X06-072

- Hale, S. A., Gardiner, B., Peace, A., Nicoll, B., Taylor, P., & Pizzirani, S. (2015). Comparison and validation of three versions of a forest wind risk model. Environmental Modelling and Software, 68, 27–41. 10.1016/j.envsoft.2015.01.016

- Foken, T. (2006). 50 years of the Monin–Obukhov similarity theory. Boundary-Layer Meteorology, 119, 431–447.

- Raupach, M. R. (1994). Simplified expressions for vegetation roughness length and zero-plane displacement as functions of canopy height and area index. Boundary-Layer Meteorology, 71(1–2), 211–216. 10.1007/BF00709229

- Rudnicki, M., Mitchell, S. J., & Novak, M. D. (2004). Wind tunnel measurements of crown streamlining and drag relationships for three conifer species. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 34(3), 666–676.

- De Rosnay, P., Polcher, J., Laval, K., & Sabre, M. (2003). Integrated parameterization of irrigation in the land surface model ORCHIDEE. Validation over Indian Peninsula. Geophysical Research Letters, 30(19).

- Gardiner, B. A., & Stacey, G. R. (1996). Designing forest edges to improve wind stability. COMMONWEALTH FORESTRY REVIEW, 75, 349–349.