1The energy budget¶

1.1OK: The surface energy budget: principle and main equation¶

ORCHIDEE’s energy budget follows a "big-leaf" approach, in which the surface (of temperature (K) and saturated humidity ()) is considered as a layer of infinitesimal thickness that exchanges with the atmosphere. The energy budget of the surface is based on two main equations. The first corresponds to the radiative budget at the surface:

Where, (W/m) is the net radiation at the surface, and (W/m) are the downwelling long- and short-wave radiations received respectively from the atmosphere and the sun, and and (W/m) are the upwelling long- and short-wave radiations emitted and reflected by the surface.

The second equation represents how the energy available at the surface () is used. By heating the surface, the absorbed energy is either re-emitted to the atmosphere under the form of convective fluxes, latent and sensible heat fluxes ( and respectively - ) or transmitted to the ground through the ground heat flux ( - ). The resulting equation enables us to calculate the evolution of the temperature of the surface ( being the surface heat capacity ).

At equilibrium, the surface energy budget equation corresponds to:

1.2OK: Radiative transfers¶

As presented in section 1.1, the radiative budget equation allows us to calculate the amount of energy absorbed by and available at the surface. It is composed of net short- and long-wave radiation budgets.

1.2.1OK: Short-wave radiations budget¶

The short-wave radiation budget calculates the amount of solar radiation absorbed by the surface. Incoming short-wave radiation () is an input variable of ORCHIDEE. The upwelling short-wave radiation () represents the amount of solar radiation that is reflected to the atmosphere, as a function of the albedo () of the entire grid-cell. Section 1.3 details the computation of the albedo for all sub-grid tiles.

1.2.2OK: Long-wave radiations budget¶

The incoming long-wave radiation emitted by the atmosphere and received by the surface () is, as for the incoming solar radiations, an input of ORCHIDEE.

The upwelling long-wave radiation () represents the emissions of the Earth surface, which is assumed to behave as a grey-body of emissivity :

Where W.m.K is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant.

1.3Surface albedo calculation¶

1.3.1Grid cell albedo¶

The albedo scheme divides the solar spectrum into two wavelength bands: visible (VIS) and near-infrared (NIR), with a separation at XX nm. For each domain, the overall grid cell albedo result from the combination of the albedo of specific grid cell components. Overall, the surface is divided into three compartments: bare soil with fractional cover , vegetated surfaces with fractional cover , non-biological surfaces with fraction cover .

For the vegetated cover, the maximum surface occupied by each PFT is divided into two parts for the radiative transfer scheme (see section below): a fraction covered by leaves and a fraction corresponding to bare soil which represents gaps in the canopy or the absence of leaves. These fractions thus evolve over time. For each grid cell the different bare soil fractions are grouped together with the same albedo, i.e. the so-called background albedo. Overall the surface is thus divided into three compartments: bare soil (bs), vegetation cover (veg), non-biological cover (nobio).

In addition, each of these land surface types is further divided between snow covered and snow-free fractions. For the snow covered fractions, the calculation of the albedo follows a more complex scheme that depends on snow age with a different formulation for the non-biological surface (see details below).

The overall albedo is thus calculated as a surface area-weighted mean of the albedo of each compartment:

Where vegetation albedo () is defined as the combination of bare soil albedo () and leaf albedo for each vegetation type (), weighted by their fractions:

Note that as such the scheme overlooks the effect of vegetation shading the bare soil for sparse canopies, in addition to giving the background for all PFTs the same albedo properties as bare soil fraction of the grid. Snow is allowed to cover both vegetated and non-vegetated areas based on the amount of snow present (see section xxxx). Note also that there is no dependence of the background albedo on soil humidity (i.e, lower albedo when the soil is humid), which may be a limitation in regions with large bare soil fractions.

1.3.2Vegetation albedo¶

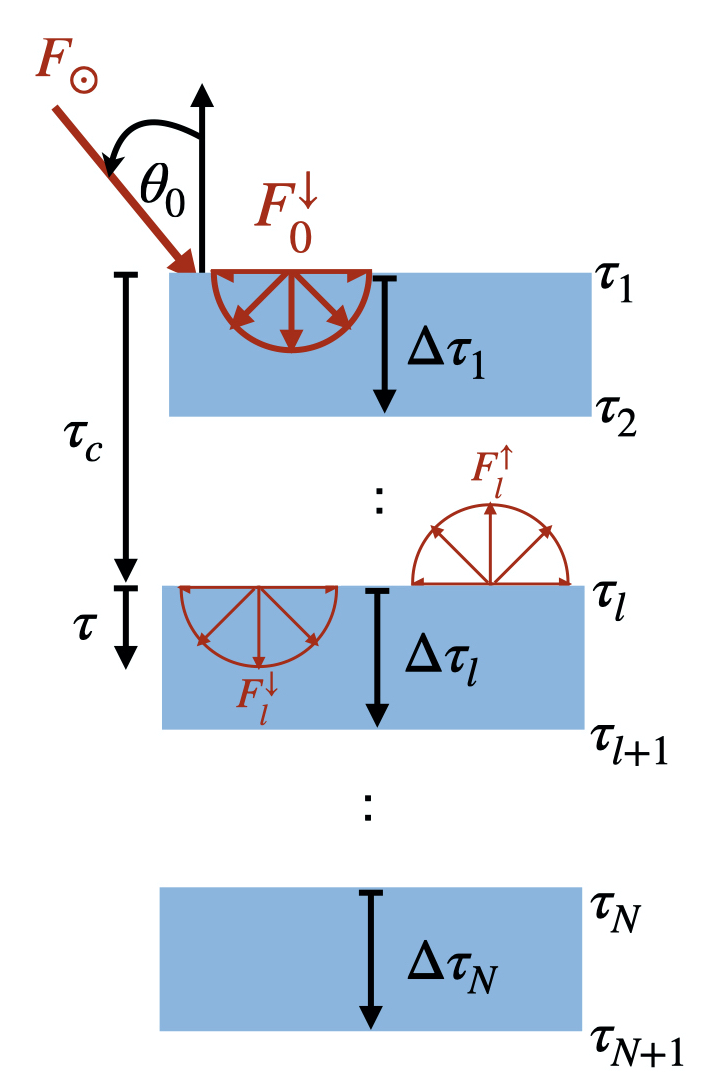

Figure 3:Schematic representation of RT through a multilayer medium. The incoming solar flux is incident at an angle with the surface normal. The medium is split into layers, with an optical depth of for each layer. The total optical depth above the th layer is , while gives the optical depth within a layer measured from the top of that layer. For each layer , the downward diffuse flux is partially scattered and absorbed, giving an upward diffuse flux .

We developed a two-stream multilayer matrix-based radiation transfer (RT) solver for the vegetation canopy based on Toon1989. We formulated the RT process as a system of linear equations that considers the interactions of radiative fluxes within and between multiple layers. This approach is particularly well suited for complex vegetation canopies for which their vertical heterogeneity can significantly impact RT. In the two-stream approximation, the basic equations for the upward () and downward () diffuse fluxes are given by Meador & Weaver, 1980Toon1989:

The gamma coefficients (, , , and ) are key parameters in the two-stream approximation that prescribe the scattering and absorption properties of the medium and are thus essential in determining the radiative fluxes within each layer. In particular, , and relate to the interactions of upward and downward fluxes, while and represent the source terms associated with scattering and absorption processes. The values of these coefficients can be derived from various approximation methods such as the Eddington approximation, quadrature, and -methods Meador & Weaver, 1980. In Eqs. (11), is the optical depth, is the single-scattering albedo, is the incident flux at the top of the canopy, and is the cosine of the solar zenith angle.

When in Eqs. (11) is substituted with , is replaced by , is taken as , is redefined as , is set equal to , and is replaced with (leaf area index) the two-stream RT equations for the vegetation canopies are obtained Sellers, 1985Dickinson1983Pinty et al., 2006:

Extending the single-layer two-stream model [Eqs. (11)] to multiple layers involves calculating the fluxes within each layer, considering the cumulative optical depths . In a given layer , the fluxes are expressed as follows:

where

Equations (13) give the analytical solution for Eqs. (11), where is the optical depth within each layer, is the cumulative optical depth at the top of each layer (Fig. 3). The coefficients and are derived from the boundary conditions and the continuity at the interfaces between the layers. For numerical stability and to keep all arguments to the exponential terms negative, the variables and as in Eqs. (15) are introduced. This mitigates the risk of numerical overflow or underflow, improving the stability and accuracy of the solver.

In these equations, represents the total optical depth of the layer (Fig. 3). The downward and upward fluxes then read:

In multilayer matrix-based RT, flux continuity and boundary conditions are maintained using a matrix of coefficients. The continuity equations for upward and downward fluxes at the interfaces of layers and are given by:

Using Eqs. (16), Eqs. (17) can be expressed as a system of linear equations:

where the coefficients , , , and are defined as:

We derived a tridiagonal system of equations to reduce computational efforts. The following steps outline the derivation process. Multiply the first equation in Eqs. (18) by and the second by , subtract the resulting equations to eliminate , leading to a new equation relating , , and . Multiply the second equation in Eqs. (18) by and the first by , subtract these results to eliminate , leading to another new equation that relates , , and . The final system of equations reads:

where the coefficients , , and , , are derived from the original coefficients , , , and the source terms , .

The downward diffuse flux at the top of the multilayer structure is equal to any incident diffuse flux. In addition, the upward flux at the bottom of the multilayer structure is equal to the product of the downward flux and the reflectance of the surface (), i.e. the incident flux reflected at the surface is diffuse. Hence, boundary conditions at the top and bottom boundaries are as follows:

We need to solve a tridiagonal system ( equations) to determine , , , [Eqs. (20)] and the related variables such as and . We use the standard method of tridiagonal solving, known as the Thomas algorithm. This algorithm is efficient for solving tridiagonal systems, as it reduces computational complexity compared with general matrix solvers.

Several key parameters need to be precalculated to model RT in the vegetation canopy. These are , , , , and . The function , known as the asymmetry factor of the phase function, is given by Myneni et al., 1989:

where and are the probability density functions of leaf normal inclination and azimuth, respectively. Several common functions exist for the probability distribution . For instance, the planophile function is given by , while the erectophile function is defined as . The plagiophile function is expressed as , and the extremophile function is represented by . The function is in the spherical case () while the uniform function is . Once the function has been determined, the other parameters can be directly derived. These are:

where is the reflectivity and is the transmissivity of vegetation (leaf). The last two equations in Eqs. (23) represent the back-scattering parameters (, ) for the diffuse and direct beams, respectively, as defined by Pinty et al. (2006). However, these two parameters need to be adjusted for other cases. In Dickinson1983Sellers (1985)Oleson et al. (2010), the back-scattering parameter for the diffuse beam is defined as

where is the mean leaf inclination angle relative to the horizontal surface. The back-scattering parameter for direct beam, , reads Dickinson1983Sellers, 1985Oleson et al., 2010:

where , the single scattering albedo of the canopy, is given by

1.3.3OK: Background and bare soil albedo¶

We combine into a single variable referred as soil albedo i) the background albedo that corresponds to the albedo of the soil under a vegetation cover and that is used as a boundary condition of the vegetation radiative transfer scheme to compute the overall vegetation albedo (see section above) and ii) the bare soil albedo from non-vegetated surfaces (i.e. Bare soil PFT).

Currently, there are two options to define the albedo of the soil. The first option (the default) is a spatially and temporally variable soil albedo, derived from MODIS satellite observations (Ref) using an extensive optimization procedure (see https://orchidas.lsce.ipsl.fr/dev/albedo/optimization.php). A 3-D field (longitude, latitude, time) of soil albedos was derived at a 1° spatial resolution and for a climatology of 12 months. The computation arises from an inverse procedure (similar to Pinty et al. (2011)), where for each 1° grid-cell the monthly soil albedo results from an optimization that accounts for vegetation albedo (see above) and snow albedo (see below). The second option corresponds to the use of a mean value (fixed in time) for each plant functional type that the user can easily prescribe.

1.3.4Snow albedo¶

The snow albedo is computed following the formulation of Chalita & Le Treut (1994) for each PFT, following the equation:

represent albedo of old snow and the sum of and is the albedo of fresh snow. is the time constant of the albedo decay of snow in days and the age of snow parameterized as follows:

where is the maximum snow age, is the amount of snowfall during the time interval and is the solid precipitation constant of snow age. Grid point albedo is weighted according to the fraction of each PFT, distinguishing between forested and grasses and crops PFTs.

For forest PFTs, the albedo is weighted with , the maximum cover fraction of a PFT, assuming that even snow-covered vegetation remains visible. For grasses and crops PFTs, the albedo is weighted with , the fraction of vegetation that covers the soil. When is lower than , the albedo of the snow on the baresoil is used. Baresoil snow albedo is weighted by with

1.3.5Ice sheet and glacier albedo¶

The non-biological compartment currently represents area covered by ice sheet or glaciers. Low surface air temperatures found in this regions slow down the snow metamorphism which is why albedo evolution is specific to these regions. This effect is accounted for with the function :

where and are tuning constant.

1.4Turbulent transfers¶

1.4.1OK: Main equation for sensible heat, latent heat and momentum fluxes¶

As shown in the surface energy budget in Eq. 6, part of the energy received at the surface is transferred to the atmosphere through turbulent fluxes. These turbulent exchanges are typically represented by three main fluxes: the sensible and latent heat fluxes, which are driven by heat and moisture exchanges between the surface and the atmosphere, and the momentum flux, which represents the drag exerted by the atmosphere on the surface.

Over the grid cell, ORCHIDEE explicitly computes the turbulent fluxes of sensible and latent heat (W m) between the surface and the atmosphere. These fluxes are represented using the diffusive formulation of Budyko (1961) and can be expressed as:

Here, is the air density (kg m), is the specific heat capacity of air (m s K), is the latent heat of vaporization (or sublimation in the case of a snow-covered surface) (J kg), is the surface temperature (K) and is the saturated specific humidity at (kg kg), and are the atmospheric temperature and specific humidity (K and kg kg), represents the combined effect of physiological and physical resistances that reduce the actual evapotranspiration relative to the potential evapotranspiration () (unitless) (see Section 1.6), and is the aerodynamic resistance (s m). The aerodynamic transport model used to compute the aerodynamic resistance is described in section 1.4.2, while the resistances for sensible and latent heat fluxes are detailed in sections 1.5 and 1.6, respectively.

Although the momentum flux itself is not computed directly in ORCHIDEE, it represents the drag force that generates turbulence and determines the efficiency of heat and moisture transfers through its control on aerodynamic resistances. The zonal () and meridional () components of the momentum flux can be expressed as:

Where and are the zonal and meridional wind components at the surface (assumed to be zero at the roughness height), and are the corresponding wind components in the atmosphere (m s), and is the aerodynamic resistance (s m).

1.4.2OK: Aerodynamic transfer: roughness length and drag coefficients¶

Does this section describe the different options in ORCHIDEE? For example, rough_dyn, use_ratio_z0m_z0h, RATIO_Z0M_Z0H, and use_height_dom. The parameter names should not neceassarily be mentioned but the different options should as they are referred in section 1.

The efficiency of turbulent fluxes introduced in the previous section depends on how the surface interacts with the atmosphere, which is captured through drag coefficients and roughness lengths. When ORCHIDEE is coupled with LMDZ, the drag coefficients are provided by LMDZ, while ORCHIDEE computes the roughness lengths. In offline mode, ORCHIDEE calculates both the drag coefficients and the roughness lengths directly. Although the energy budget is resolved at the grid-cell scale, the drag coefficients are calculated for each PFT, as they depend on vegetation structure, and then aggregated to obtain a grid cell average.

In offline mode, the roughness length is first computed for bare soil (m), as well as the drag coefficients for heat and momentum (unitless) using the von Karman constant:

Where is the fraction of snow on vegetated area, and is the bare soil roughness length set to 0.01m.

Where is the total evaporating bare soil fraction, is the von Karman constant (unitless), is the maximum height of the first atmospheric layer (set to at least 10m), and a constant representing the ratio between and , set by default to 1 for all PFTs.

Then for each vegetated PFT, several options exist to compute each of these two roughness lengths, which can be combined for a given simulation.

A dynamical computation uses the formulation proposed by Ershadi et al. (2015) based on the initial work of Su et al. (2001) for , which is calculated as:

with the canopy height (m), the displacement height, assumed equal to , the von Karman’s constant and , the ratio of friction velocity to the wind speed at the top of canopy.

The roughness length for heat is calculated, assuming an exponential relationship between and , with the following equation:

with the Stanton number (see Appendix E of Ershadi et al. (2015) for a full description).

It is also possible to use fixed ratios to define the roughness height for momentum as a fraction of the canopy height, and the roughness height for heat as a fraction of the roughness height for momentum.

Using these values of roughness lengths, the drag coefficients for heat and momentum (unitless) are computed following:

Where is the fraction of vegetated PFT. Note that in the case of forest PFTs, is set to because trees trunks influence the roughness even without leaves, while for grassland PFT, they influence the roughness only during the growing season. is the PFT vegetation height, and is a roughness scaling factor set to 0.0625 for all vegetated PFTs (unitless).

Then, for each none vegetated surface, the drag coefficients for heat and momentum are computed in a similar way:

Where is the fraction of the non vegetated surface, and is the roughness height of the non vegetated surface set to 0.001m.

Finally, the grid-cell drag coefficients are obtained by summing the fraction-weighted contributions from bare soil, vegetated PFTs, and non-vegetated surfaces. For vegetated areas, the total is normalized by the effective vegetated fraction to ensure consistent weighting across surface types.

Then, at the grid cell level, the roughness length for heat and for momentum are calculated based on the inversion of the calculation of the drag coefficients aggregated over the grid cell ( and ):

The zero-plane displacement height is also computed as a fraction of average vegetation height:

Where is the average vegetation height (m), and is a factor to calculate the zero-plane displacement height (unitless).

The grid cell effective roughness height is computed as the difference between the average vegetation height and displacement height:

Note that the vertical reference for heights differs between the land and atmospheric components: in ORCHIDEE, heights are expressed relative to the canopy top or to , while in LMDZ they are referenced from the displacement height. Therefore, provides a consistent means to convert between these reference levels.

The aerodynamic drag coefficient determines the strength of turbulent exchanges between the land surface and the atmosphere. It depends on both surface roughness and atmospheric stability, which is expressed through the Richardson number . is defined as the ratio of the two source terms for turbulent kinetic energy: buoyancy and wind shear, which depend on the gradient of temperature near the surface and on the surface wind speed:

Where is the height of the first atmospheric layer (m), is the gravitational constant, is the wind speed (), and and are the virtual temperature of the atmosphere and the surface (K).

Positive values correspond to stable conditions (suppressed turbulence), negative values to unstable conditions (enhanced turbulence), and corresponds to neutral conditions.

The neutral drag coefficient (assuming neutral atmospheric stability) is computed as:

The final stability-corrected drag coefficient is derived from and a stability function from Louis et al. (1982), which depends on the sign of :

Where (unitless).

It must be noted that when ORCHIDEE is coupled with LMDZ, ORCHIDEE does not fully compute the drag coefficients. Instead, it computes only the neutral coefficients and provides LMDZ with grid-cell effective roughness lengths for the grid cell:

LMDZ then computes the drag coefficients using the values of the surface layer for and its own stability function .

The formulation for is similar for unstable cases, but for stable cases, functions from King et al. (2001) are used:

With , (unitless).

1.5Sensible heat flux - associated resistance¶

As presented in section 1.4.1, the sensible heat flux is expressed as:

The exchange is thus controlled by the aerodynamic resistance (), which represents the efficiency of turbulent transfer of heat between the surface and the atmosphere:

Where is the horizontal wind speed () and is the drag coefficient (unitless) described in section 1.4.2.

1.6Latent heat flux components - associated resistances¶

As seen in section 1.4.1, at the grid cell scale, the latent heat flux (W m) is defined by Eq. 33 and, when expressed in water units, corresponds to the actual evapotranspiration (kg m s). It can also be expressed in terms of potential evapotranspiration ( in kg m s) as:

Where is the dimensionless stress factor that accounts for physiological and physical resistances to water transport from the surface to the atmosphere (as presented in Eq. 33), and is the latent heat of vaporization (or sublimation in the case of a snow-covered surface) (J kg).

In the approach of Budyko (1961), represents the amount of water that would evaporate if the surface was completely wet, and is calculated using the temperature of a hypothetically wet surface (K):

Where is the air density (kg m), is the saturation specific humidity at (kg kg), is the atmospheric specific humidity (kg kg), and is the aerodynamic resistance (s m).

Manabe (1969) proposed a simplification widely used in land surface models: computing using the actual surface temperature instead of . While this avoids the need to calculate a separate energy balance for a wet surface, it leads to an overestimation of , because > and is a function that increases with temperature.

To avoid this overestimation, Milly (1992) introduced a correction factor that reduces based on the stress factor as the difference between and increases. The corrected potential evapotranspiration (kg m s) is therefore expressed as:

Where is the corrective factor of Milly (1992) (unitless) calculated as:

Here, is the specific heat capacity of air (m s K), is the surface emissivity (unitless), and is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant (W m K).

While the actual evapotranspiration flux is computed at the grid-cell scale, it can be partitioned into its main components, representing the different pathways of water transfer to the atmosphere:

Floodplain evaporation

Snow sublimation

Canopy interception loss

Canopy transpiration

Bare soil evaporation

A -resistance scheme is used to partition the total evapotranspiration flux into its individual components. For each process , a coefficient is computed, representing the combined effect of the aerodynamic resistance and any process-specific resistance, scaled by the fraction of the grid cell over which the process occurs.

In this framework, quantifies the relative contribution of process to the total resistance-limited evapotranspiration.

Each component of the evapotranspiration flux (kg m s) can then be computed as:

By construction, the sum of the flux components recovers the total resistance-controlled evapotranspiration: .

Table 2 describes the different components of , their corresponding grid-cell fraction, the resistances applied to the flux and the evapotranspiration used to calculate the flux.

Table 2:Components of the latent heat flux and their corresponding fractions, resistances and evapotranspiration used for their calculation.

| Flux | Fraction | Resistances | ETP |

| Floodplains evaporation | |||

| Snow sublimation | |||

| Canopy interception loss | |||

| Canopy transpiration | |||

| Bare soil evaporation |

1.6.1Floodplain evaporation¶

The floodplain evaporation flux is calculated over the portion of the grid-cell covered by floodplains and is primarly controlled by the aerodynamic resistance .

The calculation uses a prediction-correction approach. A first estimate of the resistance factor for floodplain evaporation is based on and the ratio between the corrected and uncorrected potential evaporation fluxes:

The predicted floodplain evaporation is:

If this predicted evaporation exceeds the water available in the floodplain reservoir over the model timestep , is reduced proportionally to conserve water:

The final floodplain evaporation flux is then computed as:

1.6.2Snow sublimation¶

The snow sublimation flux is calculated over the fraction of the grid-cell covered by snow (see Section 1.4.3.5), including contributions from vegetated and non-vegetated surfaces (ice, lakes, cities, etc). This flux is controlled solely by the aerodynamic resistance .

The calculation follows a prediction–correction approach. First, a resistance coefficient for snow sublimation is estimated for each of the contributions from vegetated and non-vegetated surfaces:

For the vegetated surface:

Here, is the fraction of the grid cell occupied by non-vegetated surfaces, and is the fraction of vegetation covered by snow.

The predicted sublimation flux on the vegetation is calculated as:

If the predicted sublimation over the model timestep exceeds the available snow mass on the vegetation , is reduced proportionally to conserve snow:

Similarly, for each non-vegetated surface type :

Here, is the fraction of the grid cell of non-vegetated type , and is the fraction of that surface type covered by snow.

The predicted sublimation flux on the non-vegetation surface type is computed as:

If the predicted sublimation exceeds the available snow mass on this surface type , is reduced proportionally to conserve snow mass:

Finally, the total resistance coefficient for snow sublimation is computed as:

This corrected resistance coefficient is used to compute the actual snow sublimation flux (reduced by flooded surfaces):

1.6.3OK: Interception loss¶

The canopy interception loss flux is calculated for each PFT over the fraction of vegetation that holds intercepted water . This flux is controlled by the aerodynamic resistance and a structural resistance (s,m), which accounts for reduced air mixing within the canopy. is fixed for tree and herbaceous PFTs.

The calculation of also follows a prediction-correction scheme. First, the resistance coefficient for interception is estimated based on (see Section 1.2 and 148), the vegetated fraction of the PFT , and :

The predicted interception flux is then:

To ensure mass conservation, if the predicted flux over the model timestep exceeds the total intercepted water storage , is reduced to ensure that the evaporation does not exceed the available water:

In case of dew formation, the same framework applies but the wet fraction originates from dew deposition rather than rainfall interception. The resistance factor for dew depends on the fraction of dew on the leaves (154):

The total interception coefficient then includes both rainfall and dew contributions:

The final canopy interception loss flux, reduced by flooded and snow-covered surfaces, is then expressed as:

1.6.4Canopy transpiration¶

The canopy transpiration flux is calculated for each PFT over the fraction of the PFT covered by vegetation . The flux is controlled by the aerodynamic resistance and a stomatal and boundary layer resistance (s m).

The leaf resistance is expressed as:

Where is the maximum cover fraction of the PFT, and is the stomatal resistance integrated over the whole canopy.

The total stomatal resistance is computed from the stomatal conductance calculated in the photosynthesis model (Section 1.2) for each LAI layer , as follows:

where is the stomatal conductance of layer (m s), and is the leaf area index of layer (m m).

The transpiration resistance coefficient is then computed as the reduction of the aerodynamic flux by the leaf resistance, considering the fraction of vegetation covered by the PFT :

Finally, the actual canopy transpiration flux for the PFT, accounting for reductions due to flooded surfaces and snow cover, is given by:

1.6.5OK: Bare soil evaporation¶

Does this section describes the do_rsoil option? It should not necessarily mention the parameter name but the option should be mentioned as it is referred to in the description of the configuration in Section 1.

The bare soil evaporation flux component follows a two-steps prediction-correction scheme, as detailed in section 1.5 and summarized below.

First, a predicted bare soil resistance coefficient is calculated for each soil column . It is computed based on an initial estimate of the bare soil evaporation flux , derived from the soil water budget. This flux represents the amount of water that the soil column can supply over the timestep , given its current soil moisture profile, and is weighted by the soil tile fraction . In particular, the current water balance depends on both the bottom and top fluxes of each soil column. The top flux is determined by the corrected potential evaporation , which is limited by a soil resistance for each soil tile , scaled by the aerodynamic resistance (see Eq.196). The soil resistance, presented in Eq.195, constrains soil evaporation as soil moisture decreases, following Sellers et al. (1992).

The bare soil evaporation estimate is then normalized by the potential evaporation to compute the resistance factor for a given soil column :

This resistance factor is then averaged over the grid cell ():

Next, a correction is applied to ensure mass conservation, since the sum of canopy interception loss, canopy transpiration, and bare soil evaporation cannot exceed the total available water flux for these processes. In terms of stress factors, this means that the sum of , , and cannot exceed 1. If this limit is exceeded, bare soil evaporation is reduced so that intercepted water evaporation and transpiration can proceed at their calculated rates. In that case, is reduced to :

Finally, the corrected stress factor is used to compute the actual bare soil evaporation flux (reduced by flooded and snow-covered surfaces):

1.7Soil thermodynamics¶

1.7.1Soil thermodynamics model¶

The soil thermodynamic model in ORCHIDEE was developed by coupling heat conduction with the energy transferred by liquid water transport in the soil vertical direction, as well as latent heat due to soil freezing/melting (Hourdin (1992); Wang et al. (2016); Gouttevin et al. (2012)):

where and are volumetric heat capacities (J m K) of soil and liquid water, respectively; is the volumetric soil moisture (m m); st stands for the soil texture; is the soil temperature (K); is the time (s); is the soil depth (m); is the soil thermal conductivity (J m s K); is the flux density of liquid water (m s); is the ice density (kg m); is the latent heat of fusion (J kg); is the volumetric ice content (m m). The last term is optional and represents the latent heat source/sink term due to the freezing and melting of the soil water (Gouttevin et al. (2012)). During freezing, latent heat release delays the progression of the freezing front. In contrast, latent heat consumption counteracts warming as a frozen soil layer reaches the freezing point.

For numerical computation, equation 92 can be rewritten as:

where includes the volumetric heat capacity of the soil but also a term representing the latent heat impact (Gouttevin et al. (2012).

At the surface, the energy budget equation is:

where is the soil surface temperature (K); is the soil heat flux due to heat conduction process; , , and LF are the net radiation, sensible heat and latent heat flux respectively (W m); is the ‘layer’ heat capacity per unit area (J m K) and is related to the thickness of the first soil layer.

The Equation 92 is solved by using an implicit finite difference method. The soil temperature and the soil heat flux are calculated at the node and at the interface of each layer, respectively. The evolution of the temperature in the middle of the layers is given by ():

The temporal evolution of the temperature in the first layer is calculated as the difference between the total fluxes at the surface (atmospheric radiative fluxes, soil radiation and turbulent fluxes) and the conductive flux at the bottom of the first layer:

The soil surface temperature () is calculated from the surface energy balance equation (see section ??), and it is used as boundary forcing for calculating the subsurface soil temperature. The is linked with the soil surface temperature through:

The heat flux is assumed to be zero at the bottom layer ():

1.7.2Soil properties: thermal conductivity¶

Soil thermal conductivity and soil heat capacity are important parameters to determine the thermal evolution of the soil in depth. These parameters strongly depend on soil composition, including soil texture and soil moisture. The soil thermal conductivity () is calculated with the Johansen’s method (Johansen (1975)) by interpolating between a dry and a saturated conductivity according to the Kersten number described below.

where and are the dry and saturated thermal conductivity, respectively (W/m/K).

The Kersten number depends on the state of the water in the soil (liquid or solid) and on the degree of saturation , corresponding to the fraction of porosity occupied by liquid water and ice (), with , and being the porosity, and the volumetric liquid and solid water contents, respectively. and are calculated in the hydrological module (section 1.7.11). For unfrozen soils (Peters-Lidard et al. (1998)):

while for frozen soils, .

The dry conductivity is determined according to the soil’s porosity that depends on the soil texture of the grid cell, and is estimated with the following equation:

Finally, the saturated conductivity is a weighted average of solid conductivity , liquid water conductivity and ice conductivity when the soil is saturated ().

For mineral soils, solid conductivity is determined by separating the quartz and the other minerals, as quartz has a very large conductivity compared to other minerals. The soil texture provides quartz contents , enabling the calculation of the solid conductivity :

1.7.3Soil properties: heat capacity¶

The soil heat capacity is calculated as the sum of heat capacities of dry soil and liquid and solid water:

where , and are the volumetric soil heat capacities for dry soil, liquid water and ice, respectively (J/m/K). The parameters and depend on the soil texture (values are given in Table 1). and are the volumetric liquid and solid water contents, and are calculated in the hydrological module.

1.7.4Impact of soil organic and mineral composition on thermal properties¶

In ORCHIDEE, another parameterization (Cuynet et al. (2025)) can be activated to include the impact of soil organic matter on soil thermal properties (heat capacity and thermal conductivity). This configuration accounts for the spatial diversity of soil textures and the different amounts of organic and mineral matter that can be present in the soils. It uses external maps of bulk density of fine matter, soil organic carbon concentration, and volume fraction of coarse matter as input, additionally to what is being used in the standard configuration.

In fact, the thermal properties of organic matter can differ widely from those of mineral matter, as organic matter has a low thermal conductivity associated with a high heat capacity compared to mineral matter and can be more than twice as porous as mineral matter (Lawrence & Slater (2008)). To better estimate the respective impacts of each soil component, the volume they occupy in each grid cell and at each depth is estimated.

Two types of volume fraction are estimated for soil composition: a volume fraction that includes the porous space of the material, hereafter used with the notation ""; and a solid volume fraction, referring to the effective volume occupied by dense matter and excluding porous space, with the notation "". These fractions are estimated for organic matter (OM), fine mineral matter (MM) and coarse mineral matter (CM) from external maps: bulk density of fine matter (), soil organic carbon mass fraction () and volume fraction of coarse matter (). Here, fine matter is composed of organic (OM) and fine mineral matter (MM), but does not include coarse matter (CM).

In a first step, it is possible to estimate the OM mass fraction as a function of the organic carbon mass fraction of the soil, using the Van Bemmelen conversion factor (Heaton et al. (2016)) , set at 0.58 according to the literature.

Then, the solid volume fractions can be calculated:

where and are the particle densities of organic and mineral matter, respectively, and is the porosity of mineral matter.

The effective porosity of the soil is the remaining volume, and becomes:

This porosity is used to calculate the saturation ratio and the Kersten number defined in section 1.7.2 and is also used in equation 103.

The volume fractions including the pores can be calculated by assuming that the porosity of mineral matter remains the same within a soil texture, while the volume fraction of OM is estimated by removing the volumes occupied by fine () and coarse mineral matter ():

The heat capacity is now a weighted arithmetic average of the capacity of each constituent, the solid volume fractions being used as weights.

where , , , and are the solid volumetric heat capacities of organic matter, mineral matter, liquid water, ice and air respectively; and and are the volumetric contents of liquid and solid water.

The methodology to calculate the soil thermal conductivity remains the same as the one described in section 1.7.2, but the calculation of and is modified.

The solid conductivity is a geometric average of the conductivities of OM , quartz and other solid minerals , weighted by the solid volume fractions within the soil’s solids.

with being determined via the quartz content and the solid volume fractions of fine and coarse mineral matter:

Finally, the dry soil conductivity corresponds to the thermal conductivity of the soil in the absence of liquid water and ice. The dry thermal conductivities are weighted by using the volume fractions of OM and coarse and mineral matter.

where is the dry conductivity of organic matter and is the dry conductivity of mineral matter, calculated with equation 102.

1.7.5Snow thermal properties¶

In the snow covered regions, the uppermost soil layers are replaced by snow according to the snow depth. The heat capacity and thermal conductivity of snow ( and , Table 1) are used for the layers filled by snow. In the transition layer (mixed soil and snow), the heat capacity (or thermal conductivity ) is parameterized by weighting the (or ) and (or ) according to the thickness of snow () and soil.

The effective heat capacity is defined as

where xci is the specific heat of ice (2.106×103 J/Kg/K). The effective thermal conductivity of snow is from ISBA explicit snow scheme (Boone (2002)), and it is computed by: snow(θ)=+bsnowsnow+max[0,(v+bv/(Tsnow+cv))P0/P] (10) where v represents vapor transfer in the snow; p is the atmospheric pressure in hPa, p0=1×103 hPa; ρ is the snow density (kg/m3). The coefficients were from Sun et al. (1999) and Anderson (1976): αλ,v = -0.06023 W/m/K; bλ,v = -2.5425 W/m; cλ,v = -289.99 K. αλ = 0.02 W/m/K; bλ = 2.5 ×10-6 Wm5/kg2/K.

Verseghy, D. L., 1991: CLASS - A Canadian land surface schemefor GCMs. I. Soil Model. Int. J. Climatol., 11, 111–133.

When the soil is frozen, the and values are the same with that of unfrozen case, while the and are computed by taking into account the thermal properties of ice component (Gouttevin et al. (2012)):

where is the fraction of the liquid water, and it is assumed to linearly varied from 1 to 0 between 0° C and -2° C in the “freezing window”; , , are the thermal conductivity for solid soil, ice and water, respectively (W/m/K); and are the heat capacity for saturated unfrozen soil and saturated frozen soil, respectively (J/m3/K, Table X).

1.7.6Surface litter and organic matter insulation¶

Litter and groundcover vegetation (mosses, lichens) affect surface-atmosphere energy exchanges through their insulating properties. This effect has been shown to significantly impact the simulation of permafrost dynamics in the arctic when ORCHIDEE is coupled to the atmospheric model, LMDZ, Gaillard et al., 2025. It is not explicitly represented but instead, the thermal properties of the upper soil layers are modified to mimic the impact of such a surface organic layer (SOL). The surface organic layer is assumed to cover a fraction of each grid cell. This fraction is then weighted by the fraction of boreal PFTs, as mosses and lichens are almost ubiquitous in most Arctic ecosystems, but it can be extended to other PFTs.

To calculate the effect of this surface organic layer, a virtual column (not explicitly represented in the model) is defined, representing the aboveground surface organic layer (with a thickness defined by the parameter ) and the soil layers whose thermal properties are modified (down to a depth defined by the parameter SOIL_INTEGRATION_DEPTH (SID)) (add schematic ?). The thermal capacity of the virtual column is a weighted average of the surface organic layer (CSOL) and the soil (Csoil) thermal capacities:

The total thermal capacity, also taking into account the fraction of the PFT not covered by the organic layer, is the weighted average of Cvirtual column and Csoil:

where is the total heat capacity (soil and surface organic layer), the thermal capacity of surface organic layer, the soil thermal capacity (as calculated in section 1.7.3), the fraction of each grid point that contains the surface organic layer, SOLT the surface organic layer thickness and SID the soil integration depth, i.e. the depth above which soil organic layer properties are taken into account. We use , SOLT=0.03m and SID=0.03m. SOLT is consistent with the moss thickness measured in Soudzilovskaia et al. (2013). In the real world, the surface organic layer is above ground and does not directly influence soil thermal dynamics. Therefore, SID is chosen to be thin enough to allow the soil organic layer to influence surface-atmosphere energy exchanges, but to limit its effect on internal soil thermal transfers to the very top soil layers.

The approach for thermal conductivity is similar but takes into account that it is an intensive property. Therefore, the thermal conductivity of the surface organic layer column (virtual column) is the equivalent thermal conductivity of the surface organic layer and soil layers in series:

where SOL is the thermal conductivity of the soil organic layer and soil the thermal conductivity of the soil (as computed in section 1.7.2).

The total thermal conductivity is the equivalent thermal conductivity of the surface organic layer column and the soil column in parallel:

In the model, from the surface down to SID, the mineral soil capacity and conductivity are replaced by and .

The thermal properties of the surface organic layer are parameterised using observations made on mosses. In particular, the surface organic layer thermal capacity and conductivity are linearly dependent on the water content of the soil layers down to SID Soudzilovskaia et al., 2013O'Donnell et al., 2009. The thermal capacity is set at 0.29 J.m.K for a dry surface organic layer, 4.29 J.m.K for a wet organic layer and 3.26 J.m.K for a frozen surface organic layer Soudzilovskaia et al., 2013Druel et al., 2017. The thermal conductivity is equal to 0.05 W.m.K for dry surface organic layer, 0.56 W.m.K for a wet surface organic layer and 1.40 W.m.K for a a frozen surface organic layer O'Donnell et al., 2009Porada et al., 2016.

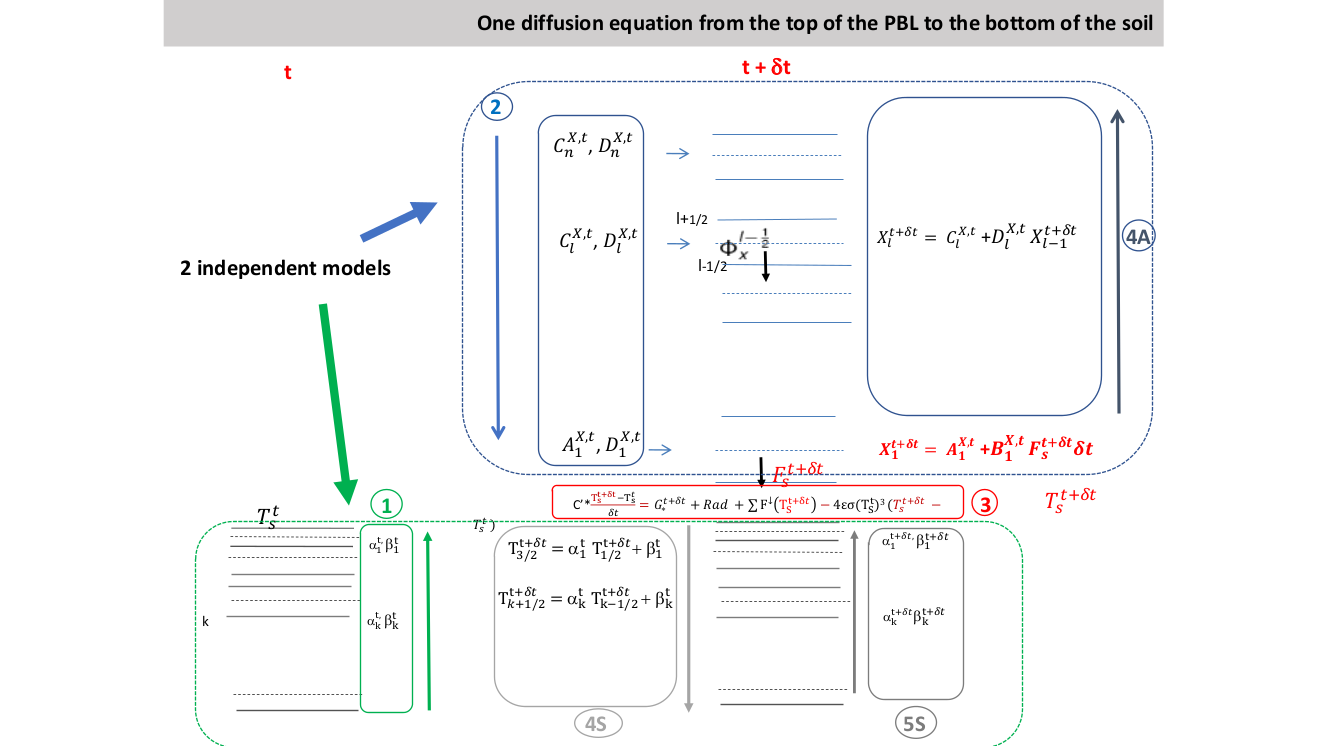

1.8Implicit resolution of the energy budget when coupled to LMDZ atmospheric model¶

To solve the energy budget at the surface, ORCHIDEE uses an approach proposed by Hourdin (1992). The numerical scheme is formally equivalent to the implicit resolution of a diffusion equation from the top of the atmosphere to the bottom of the soil but solved with two models totally independent. Using the continuity of the temperature and finite difference implicit numerical integration of the diffusion equation for the temperature the discretized surface energy balance reads

is the time step for the numerical integration it is identical for the atmospheric model and for the land surface model. However, as the radiation scheme is very expensive computationally it is not called at every time step. Using the continuity of the temperature, the surface temperature extrapolated from the temperature a level 1/2 and 3/2 in the soil. The implicit solution for the temperature into the soil allows linearly express as function of .

If denotes the depths for the level n below the surface and

The surface temperature reads

Reporting the expression of Ts obtained in (6) in equation (4) on can write:

where t and t+1 stand for 2 successive time-steps. is an effective heat capacity per unit area () and is an effective ground heat flux. These quantities together with and are evaluated when the heat diffusion into the soil is solved using an implicit scheme as well

The important aspect here is that the latter quantities can be determined in advance at the time step t for the time step t+1. At this time, to solve the surface temperature at the new time step, one needs to find the values of the turbulent fluxes and the upward LW radiation at the new time step Dufresne & Ghattas, 2009.

is computed by the GCM and is supposed not to depends from the surface temperature. For , the downward LW radiation is also supposed to be independent of the surface temperature. The upward LW radiation is estimated at the new time step with the help of a Taylor expansion.

This approach allows to take into account surface temperature variations in the land surface model surface radiation budget even though the radiation scheme is not called at each time step. However it can lead to a small energy imbalance between the atmosphere and the surface which has been estimated to about 0.2 W/m (from global multi-annual coupled simulations)

Once discretized in time and space the turbulent diffusion in the atmosphere leads to solving a linear spatio-temporal boundary values problem. The system is solved with an Euler implicit approach because the time steping requires large time steps (15mn) with respect to the typical time evolution of the turbulence. This involves the resolution of a tridiagonal system. As a consequence,

the value of the state variable X at the first level can be expressed as a function of the flux at the surface with the following expression: , where the coefficients and are function of and of the turbulent diffusion coefficient at the upper levels. They are independent of the value of X at the surface.

Using the expression of the turbulent fluxes at the surface resulting from the Monin Obukof similary theory(section xx), the potential enthalpy flux at (t+1) can be expressed as follows:

And the latent heat flux can be expressed as

using a Taylor development of the saturation water vapor specific humidity as a function . is then obtained by reporting the expression of the fluxes at the new time step into (7).

Figure 4:Schematic representation of the implicit coupling between atmosphere and land surface for the energy budget

1.9OK: Lakes energy budget¶

In ORCHIDEE, two options are available to represent lakes. In the first option (default settings), lakes are considered bare soil surfaces with corresponding energy and water budgets. When coupled to an atmospheric model (LMDZ or WRF), the Great Lakes surface processes are either handled by the ocean model (NEMO) or constrained by climatic lake surface temperatures forced to sea surface temperature (SST) observations. In the second option, lakes are explicitly modeled, and a second energy budget is computed separately at the lake-atmosphere interface based on a one-dimensional Freshwater Lake model (FLake) Mironov, 2008, allowing to compute lake thermodynamics and surface fluxes, including evaporation. However, the water balance is not maintained since the lake tile is considered an infinite water reservoir with static volume and surface area. This second option is, therefore, not available when ORCHIDEE is coupled with an atmospheric model.

1.9.1OK: Lake model for the energy budget: principle¶

FLake is a two-layer thermodynamic lake model representing a well-mixed bulk layer above a thermocline, both modeled through a self-similarity approach. The model solves the lake energy budget and calculates the energy vertical transfers and the water temperature profile. Snow, ice and sediment may be accounted for through specific parametrizations that can be activated or not. FLake has been implemented in ORCHIDEE by Bernus & Ottlé (2022) and evaluated against lake surface temperature observations over about 1000 lakes sampled in the GloboLakes database Carrea & Merchant, 2019. Lakes are represented as a separate tile within the grid cell with no connections to the vegetated part. FLake was implemented in the sechiba code since it is forced by the same meteorological variables as the vegetated part of the grid and runs at the same time step of a few minutes. The resolution of the bulk energy budgets of the mixed layer and the thermocline allows us to model the following prognostic variables: mixed layer temperature and depth, water bottom temperature, ice and snow layer top temperatures and thermocline shape factor. Compared to the original FLake model, a few refinements were brought to the shape factor and albedo parameterizations, well described in Bernus & Ottlé (2022). More recently, Titus et al. (2025) proposed to account for partial ice cover to better simulate the lake surface albedo and ice phenology in cold weather. A parameterization of the ice fraction derived from Garnaud et al. (2022) was implemented and used to compute the surface albedo of the lake tile. This development contributes to better matching the ice phenology of 200 lakes, especially the ice melting phase with a reduction of the errors in the prediction of the ice-off time, up to 18 days.

1.9.2OK: Lake model description¶

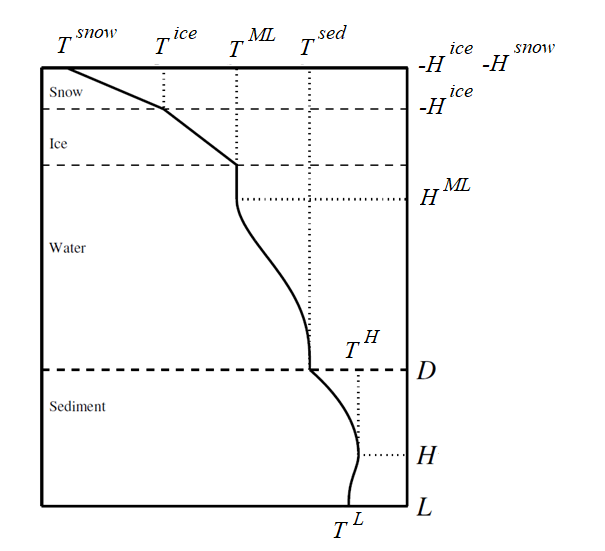

Put main equations of the model + figure potentially ? + Check all variable notations

The Flake model implemented in ORCHIDEE can predict the seasonal evolution of the vertical temperature structure within lakes at the global scale. The model described in Bernus & Ottlé (2022), was developed by A. Bernus during its PhD at LSCE. FLake is based on a self-similar parametric representation of the four mediums described within lakes: water column, sediment layer, snow, and ice layers if present, and for which, the heat budget equations are resolved. It is a bulk model where the energy budget and entrainment equations are resolved based on a two-layer representation of the mixed layer (ML) and thermocline temperatures, as well as for the sediment layer. Lake water is treated as a Boussinesq fluid (constant density except for the calculation of the buoyancy term representing natural convection). The model is fully described in many papers Mironov et al., 1991Mironov, 2008Mironov et al., 2010Golosov et al., 2018Bernus et al., 2021Bernus & Ottlé, 2022Titus et al., 2025. Here, we recall the main equations resolved in the ORCHIDEE version and the specificities linked to the model coupling and new parameterizations used. Figure 5 presents the lake temperature profiles and the 10 variables that are prognostically computed, i.e., the mixed layer temperature and depth , the water bottom temperature at the water-sediment interface , the level in the sediment layer where the temperature gradient is null and the respective temperature, the snow temperature at the snow-atmosphere interface, the ice temperature at the snow-ice interface and the snow and ice depths. Besides, surface momentum and heat fluxes are diagnosed at each time step provided by the atmospheric forcing. In ORCHIDEE, the calculations are done at the time step of Sechiba (30 minutes).

Figure 5:Schematic representation of the temperature profile in the four mediums represented in Flake (snow, ice, water and sediment layers).

1.9.3OK: Thermocline temperature profile¶

The self-similarity parameterization adopted to resolve the temperature profiles assumes that the temperature follows a universal function of the normalized depth both given by:

Where is the lake surface temperature.

Where is the temperature at depth and is the mean depth of the lake.

1.9.4OK: Energy budget equations¶

The calculation of the temperatures at the water-atmosphere and the water-sediment interfaces requires the resolution of two energy budgets: one for the mixed layer and the other for the whole lake layer:

Where is the density of water, is the specific heat capacity of water, is the incoming long wave radiation, is the incoming short wave radiation, is the heat flux at the interface between the mixed layer and the thermocline, is the albedo of water, and is the solar radiation that reaches the mixed layer.

Where is the heat flux at the lake–sediment interface, and is the solar radiation that reaches the lake–sediment interface.

The resolution of the equations requires a final closure equation with the assumption that the vertical heat flux also follows a self-similarity law:

The integration between the mixed layer depth and the lake depth allows to calculate the evolution of the water temperature at a given depth with the following equation:

Where and are two shape factors with respect to the heat flux and to the temperature respectively.

1.9.5OK: Turbulent transfers: mixed layer depth¶

To calculate the mixed layer depth, two cases are considered: if the convection is driven by the water density gradient or if it is driven by the surface wind. In the first case, the evolution of the mixed layer is given by:

Where and are empirical dimensionless constants, is the entrainment ratio and the convective velocity scale. In the second case, the conservation of the turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) allows to define an equilibrium mixed layer depth. Then, the evolution of the mixed layer depth to this equilibrium is calculated according to a relaxation time scale depending on the surface friction velocity.

1.9.6OK: Sediment layer¶

The sediment layer is parameterized with a two-layer parametric representation similar to what is done for the thermocline following Golosov et al. (2018). Empirical polynomial expressions are used to calculate the temperature profiles and the heat flux at the water-sediment interface. The attenuation depth of the annual thermal wave and its corresponding temperature are calculated whereas bottom temperature and total sediment depth are prescribed.

1.9.7OK: Ice and Snow cover¶

The vertical temperature profile in the ice and snow layers are also parameterized with a self-similarity approach. The normalized temperatures are given by the following equations, assuming linear profiles called and for the ice and snow layers respectively.

Where is the freezing temperature of water.

The resolution of the energy budgets for the two layers with the boundary conditions on the temperatures at all interfaces allows to calculate the depth of both layers and their temperatures:

Where and are the ice and snow densities, and are the specific heat capacities of ice and snow, and are the thermal conductivities of ice and snow.

Where is the latent heat of fusion of water, and is the heat flux at the water–ice interface.

Where is the snow accumulation associated with precipitation.

In these equations, the snow and ice layer albedos are key parameters determining the amount of energy available to melt the snow and ice mediums. In ORCHIDEE-FLake, the lake surface albedo is calculated according to the surface temperature. For free water, the albedo is set to a value of 0.07 which is the standard value used in FLake. In the presence of ice, possibly covered by snow, the lake surface albedo () depends on the temperature as suggested by Mironov et al. (2012) and varies between two limits corresponding to wet and dry snow (in presence of snow), and to blue and white ice (without snow), based on the same equation:

where and are respectively the minima and maxima values for ice or snow, is the snow or ice surface temperature in Kelvin, which is always lower than the water freezing point temperature, and is a fitted coefficient equal to 95.6 Mironov et al., 2012. In Flake, the minimum and maximum albedos are equal to 0.1 and 0.6, respectively, for snow and ice. They were revised by Titus et al. (2025)Bernus & Ottlé (2022) following Semmler et al. (2012)Pietikäinen et al. (2018) and Bernus et al. (2021), and set to 0.15-0.5 and 0.50-0.87 for ice and snow, respectively.

1.9.8OK: Ice cover fraction¶

In the original Flake model, the whole lake surface freezes when the surface lake temperature falls below 0°C and the ice thaws above this temperature threshold, regardless of the lake’s size. Actually, large lakes may present partial ice coverage, a feature which is important to simulate, if one wants to represent correctly the lake surface temperatures and fluxes in cold weather. To better represent such conditions, Titus et al. (2025) introduced in ORCHIDEE-Flake, the parameterization proposed by Garnaud et al. (2022) to derive the ice cover fraction from the calculated ice thickness. This fraction varies linearly between 0 when the lake is free of ice, to 1 above a certain threshold set to a critical value dependent on the wind fetch, in order to represent the fact that ice is more likely to break under the action of wind stress until it grows to a critical thickness. This critical ice thickness value may be written:

Where is the scale of the surface wind stress (set to 0.15 Pa), is the compressive strength of ice (set to 27.5 kPa) and is the lake fetch (in meters).

For each lake tile, the fetch is static and prescribed to the mean of the fetch of all the lakes falling in the tile. It is estimated at the lake level from the surface extent by assuming a circular shape and taking the diameter of this circle. Given that we did not consider lakes smaller than 0.1 due to the limitations of the HydroLAKES database, it means that the fetch values range between a few meters and a few hundred kilometers, leading to critical thicknesses ranging between 2 mm for the smallest lakes to 1.1 m for the larger ones.

The ice cover fraction of the lake tile, , is then derived from the modeled ice thickness using:

The ice fraction is used in ORCHIDEE-FLake to simulate the lake albedo through a supplementary equation, linearly linking the lake albedo to the ice fraction and accounting for the presence of snow, if any. The lake tile surface albedo is now given by:

where is the free water albedo, is the snow albedo in snowy conditions and the ice one otherwise, both derived from Eq. 142 and dependent on the surface temperature of the lake tile.

- Meador, W. E., & Weaver, W. R. (1980). Two-Stream Approximations to Radiative Transfer in Planetary Atmospheres: A Unified Description of Existing Methods and a New Improvement. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 37(3), 630–643. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1980)037<;0630:TSATRT>2.0.CO;2

- Sellers, P. J. (1985). Canopy reflectance, photosynthesis and transpiration. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 6(8), 1335–1372.

- Pinty, B., Lavergne, T., Dickinson, R. E., Widlowski, J.-L., Gobron, N., & Verstraete, M. M. (2006). Simplifying the interaction of land surfaces with radiation for relating remote sensing products to climate models. Journal of Geophysical Research, 111(D2), D02116. 10.1029/2005JD005952

- Myneni, R. B., Ross, J., & Asrar, G. (1989). A review on the theory of photon transport in leaf canopies. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 45(1–2), 1–153.

- Oleson, K. W., Lawrence, D. M., Bonan, G. B., Drewniak, B., Huang, M., Koven, C. D., Levis, S., Li, F., Riley, W. J., Subin, Z. M., & others. (2010). Technical description of version 4.0 of the Community Land Model (CLM). NCAR Tech. Note NCAR/TN-478+ STR, 257, 1–257.

- Pinty, B., Andredakis, I., Clerici, M., Kaminski, T., Taberner, M., Verstraete, M. M., Gobron, N., Plummer, S., & Widlowski, J.-L. (2011). Exploiting the MODIS albedos with the Two-stream Inversion Package (JRC-TIP): 1. Effective leaf area index, vegetation, and soil properties. Journal of Geophysical Research, 116(D9), D09105. 10.1029/2010JD015372

- Chalita, S., & Le Treut, H. (1994). The albedo of temperate and boreal forest and the Northern Hemisphere climate: a sensitivity experiment using the LMD GCM. Climate Dynamics, 10(4–5), 231–240.

- Budyko, M. I. (1961). The Heat Balance of the Earth’s Surface. Soviet Geography, 2(4). 10.1080/00385417.1961.10770761

- Ershadi, A., McCabe, M., Evans, J., & Wood, E. F. (2015). Impact of model structure and parameterization on Penman–Monteith type evaporation models. Journal of Hydrology, 525, 521–535.

- Su, Z., Schmugge, T., Kustas, W., & Massman, W. (2001). An evaluation of two models for estimation of the roughness height for heat transfer between the land surface and the atmosphere. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, 40(11), 1933–1951.

- Louis, J.-F., Tiedtke, M., & Geleyn, J.-F. (1982). A short history of the PBL parameterization at ECMWF. Workshop on Planetary Boundary Layer Parameterization, 25-27 November 1981.

- King, J., Connolley, W., & Derbyshire, S. (2001). Sensitivity of modelled Antarctic climate to surface and boundary-layer flux parametrizations. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 127(573), 779–794.

- Manabe, S. (1969). Climate and the ocean circulation. Monthly Weather Review, 97(11). https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0493(1969)097<;0775:catoc>2.3.co;2

- Milly, P. C. D. (1992). Potential Evaporation and Soil Moisture in General Circulation Models. J. Climate, 5, 209–226. 10.1175/1520-0442

- Sellers, P. J., Heiser, M. D., & Hall, F. G. (1992). Relations between surface conductance and spectral vegetation indices at intermediate (100 m2 to 15 km2) length scales. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 97(D17), 19033–19059. 10.1029/92JD01096